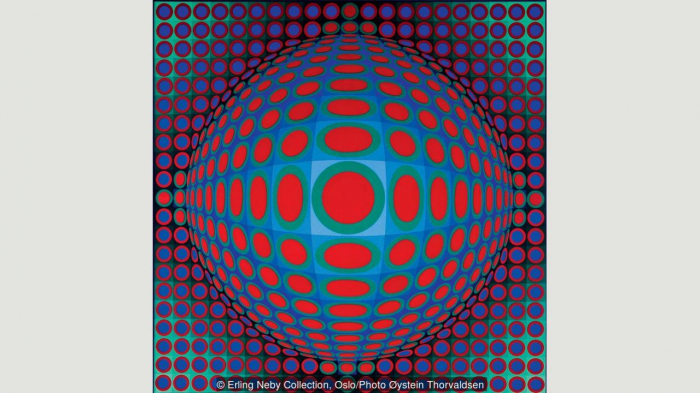

By the early 1970s, Victor Vasarely was everywhere. Regarded by historians today as the ‘grandfather’ of Op Art, the Hungarian-French abstract artist, then in his late sixties, had watched his pioneering geometric designs and hypnotising optical illusions come to represent his generation. Vasarely’s carefully calibrated patterns of bright squares and luminous circles, which make his paintings’ surfaces appear like warping space-time webs – now rippling and concave, now spinning and convex – was the hottest of hot demands.

Vega 222, 1969-1970 (Credit: Erling Neby Collection, Oslo/Photo Øystein Thorvaldsen)

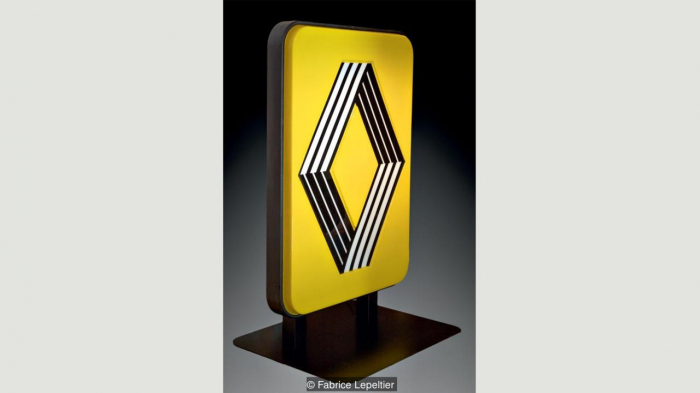

Renault, the automobile manufacturer, hired him to redesign the company’s famous logo. David Bowie hired him to create the cover art for his album Space Oddity. Most, however, simply plagiarised the poetic physics of Vasarely’s elegant grilles and melting lattices, desperate to tap into the futuristic wonder of their sleek style, without paying him a cent or acknowledging their debt.

Renault logo, 1972, by Victor Vasarely and Yvaral (Credit: Fabrice Lepeltier)

A major exhibition devoted to Vasarely, now on at Centre Pompidou in Paris, has assembled more than 300 paintings, drawings and Pop Art objects that map his long career as a tireless innovator of 20th-Century abstract art. Among the dizzying inventory of images collected for the show is a formative ink-on-paper work that stands out as pivotal to the growth of one of the most under-appreciated imaginations in modern cultural history. Created in 1938, when Vasarely was still earning his stripes as a jobbing graphic designer in Paris (having finished art school at the Bauhaus-inspired Muhely Academy in Budapest a decade earlier), the deceptively simple monochrome work belongs to a series of studies devoted to the muscular movement and mesmerising markings of the African equid.

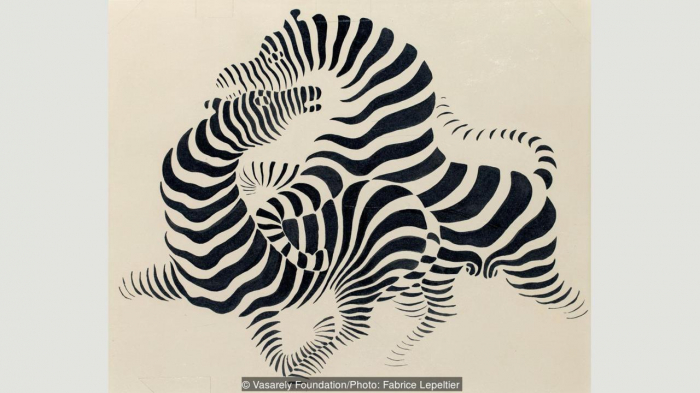

Zèbres-A, 1938 (Credit: Vasarely Foundation/Photo: Fabrice Lepeltier)

Weaving and unweaving the beast’s black-and-white stripes, the transfixing depiction of a pair of wrangling zebras strobes strangely before our eyes. The wild, striated sinews of the tussling pair in Zebres-A (1938) appear to pulsate and quiver, as if alternately kicking outwards towards the observer, beyond the image’s surface, and recoiling into the invisible absence of the empty white field from which they’ve miraculously emerged. The tangle of flexing lines is almost kinetic in the fluid, fluctuating movement it magicks from the simplest and sparest of pen-and-ink gestures.

Adding to the dislocating effect of Vasarely’s carefully controlled chaos is the sheer surprise of seeing zebras in a work of art in the first place. In the Noah’s ark of art history, it’s the horse – the zebra’s zoological cousin – that has conventionally commanded our attention, trotted out on the walls of museums and galleries. The horse, of course, runs right through the long saga of image-making from the Stone Age to the present. From the prehistoric charcoal broncos that gallop across the crude interior of the Lascaux caves to the countless stallions stitched into the Bayeux Tapestry; from the steed in Jacques-Louis David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps to the tortured neigh that whinnies at the centre of Picasso’s Guernica, horses have reigned supreme in cultural consciousness. (And that’s not even mentioning the stampede of George Stubbses out there). Zebras? Not so much, despite the fact that they, more than any animal, seem half-drawn into the real world of fully filled-in colour – suspended midway between the India ink of an artist’s draughting table and the blinding hues and havering heat of a mirage-soaked savannah.

Kroa MC, 1970 (Credit: Fabrice Lepeltier)

In Vasarely’s zebra portraits, the distinctive markings of the animal are transformed from something physical and empirical – pigment and hide – to mysterious metaphors for an almost transcendental phenomenon: the merging of the mind of the observer with the impalpable spirit of the natural world. They seem more like a sophisticated meditation on how the eye stalks the ever-elusive object of its gaze, rather than an attempt to chronicle the animal’s magnetic mien.

I can’t help wondering whether the artist may have been influenced, knowingly or otherwise, by experiments undertaken by maritime designers in the US and the UK admiralties during the first and second world wars, camouflaging their warships with markings inspired by the zebra. Believing that zebras may have evolved their distinctive stripes as a defence against predation (allegedly making it difficult for predators to isolate a single target or to assess the depth of field in which their prey moved), the British artist Norman Wilkinson proposed cloaking vessels in a jumble of angular black-and-white striations to confuse adversaries. So-called ‘razzle-dazzle’ wasn’t intended to render a ship physically imperceptible, but merely to jam the senses of the approaching enemy.

Stripes and stars

Tracing the growth of Vasarely’s imagination as it emerges over the course of the hundreds of works assembled into seven rooms of this vast exhibition, one increasingly appreciates what a game-changing revelation the dazzling hide of the zebras clearly was for the artist. Earlier figurative works of soulless, mannequin-like automatons inhabiting vacated cityscapes seem static by comparison, and show the young artist foraging around in the borrowed language of surrealism and constructivism for something authentic to his own way of seeing.

Vonal Zold, 1968 (Credit: Editions du Griffon/Sully Balmassière)

Every work by Vasarely that follows on from the zebra breakthrough seems inflected by that muscular epiphany. During the war years and after, Vasarely found himself ineluctably drawn in the direction that his hypnotic zebras were pulling – obsessed with scientific literature and ground-breaking optical theories. He found himself attempting to sync his vision with every undulation observable in the world around him, whether natural or manmade.

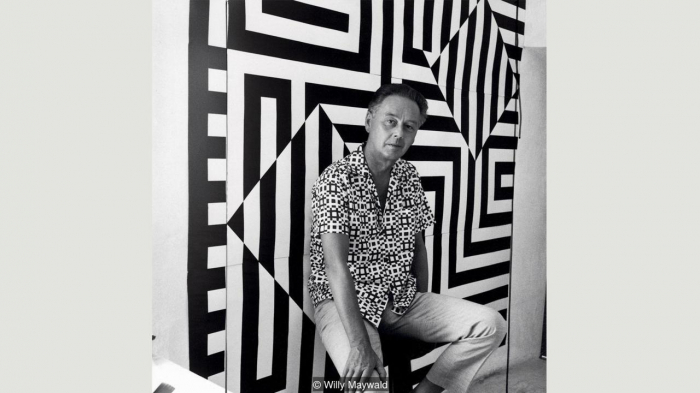

Victor Vasarely in 1960 (Credit: Willy Maywald)

In an effort to perceive an invisible architecture that underlies reality, he began scrutinising everything from the motion of the tides to the organic pattern of cracks and fissures in subway tiles. The result was a series of monochromatic works created throughout the 1940s and ‘50s that are very much in accord with the spiritual temperament of his better-known contemporaries such as Arshile Gorky, Piet Mondrian and the Swedish mystic Hilma af Klint, whose secretive work – hidden from public view during these decades – is itself now undergoing a major revival.

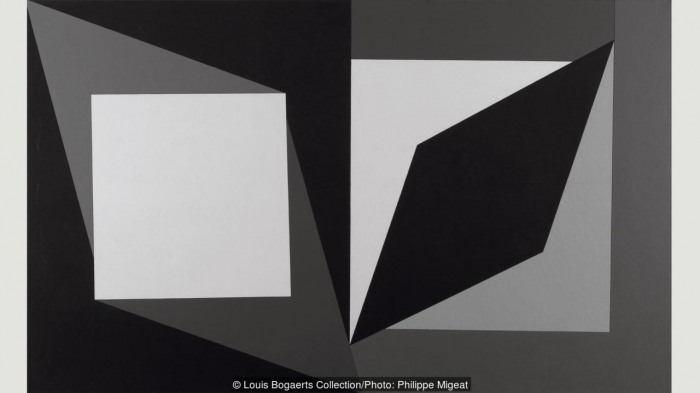

Hommage à Malévitch, 1954-1958 (Credit: Louis Bogaerts Collection/Photo: Philippe Migeat)

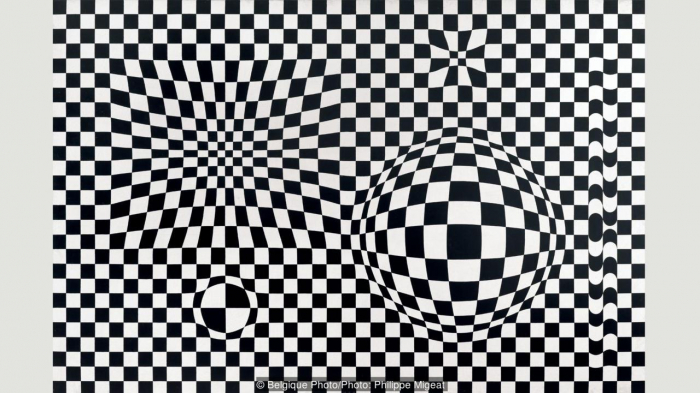

In Hommage à Malévitch (1954-58), it is as if Vasarely has taken the Russian avant-garde artist’s famous Black Square (1915), which Malevich himself believed embodied the ‘spirit of non-objective feeling… which penetrates everything’, and tied that legendary canvas to the twisting tendons of a zebra’s fierce physique, tugging it out of all proportion. The melting chessboard of Vasarely’s elastic oil-on-canvas painting Vega (1956), created around the same time as Hommage à Malévitch, seems likewise committed not so much to measuring the weight and substance of what we actually perceive in the world around us, but, paradoxically, to offering a glimpse into the unseeable forces and gravities that twist and distort our perception. Here, it feels like the memory of the zebra’s stretching and contracting stripes has been fed through a digitising scanner or the pixelating mince of a particle collider in order to decrypt the binary code of its aesthetic essence.

Vega, 1956 (Credit: Belgique Photo/Photo: Philippe Migeat)

By the 1960s, Vasarely had hit his stride in establishing what he believed were the archetypal gestures of a universal language, one that was fully in harmony with the brave new scientific discoveries of his age – “worlds which”, he would write, “up until now, have escaped the investigation of the senses: the world of biochemistry, waves, fields, relativity”. Vibrant colour, which he had used relatively sparingly in the years since depicting his first zebra, begin to seep back into the artist’s work as a new generation of artists such as Bridget Riley, whose own engrossing lines strummed in tune with his, helped give his innovative vision corroborating traction.

Szem, 1970 (Credit: Editions du Griffon/Sully Balmassière)

However increasingly complex the algorithms that generated works such as Vonal Zold (1968) and Szem (1970) may initially seem, the verve of their pulsing vortices and the rhythm of their thrumming music can be traced back, decades earlier, to the bold prance and dance of zebra stripes that caught the artist’s soul off guard, and trampled it into genius.

BBC

More about: ART