The tiny speck of stardust was found inside of a chondritic meteorite in Antarctica, having originally been hurled into space by an exploding star that died even before our own sun existed.

Little pieces of grain like the new discovery are thought to help create the early mix of materials that helped form the sun and our planets – and, eventually, life. But they are rarely seen, because it is so difficult for them to survive the chaos of the beginning of a solar system.

Now scientists hope the small and lucky grain could offer an insight into the conditions that helped form everything that surrounds us.

"As actual dust from stars, such presolar grains give us insight into the building blocks from which our solar system formed," said Pierre Haenecour, lead author of the new paper published in Nature. "They also provide us with a direct snapshot of the conditions in a star at the time when this grain was formed."

The grain has been named LAP-149 and is the only known piece of graphite and silicate grains that scientists can trace back to the particular type of stellar explosion that it managed to survive. After being cast out by that eruption, it flew through space and arrived in the area that is now our solar system, getting caught up in a primitive meteorite.

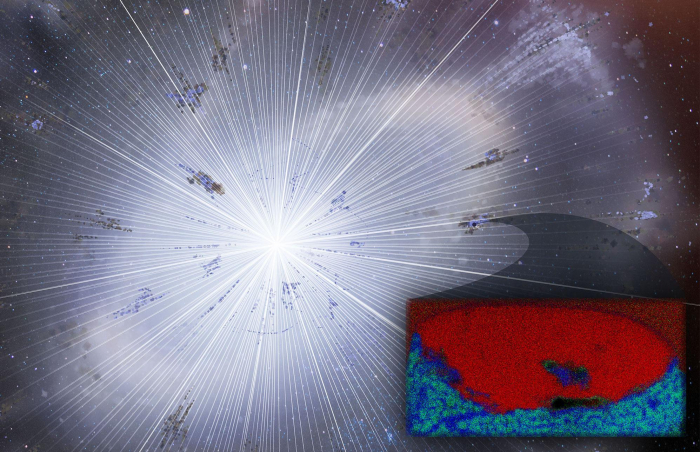

Novae like the one that threw out the speck of dust happen when a binary star system includes the core remnant of a dying star known as a white warf, attached to another star that is either a main sequence star or red giant. As the white dwarf fades, it saps away the substance of its bigger companion – and once it is big enough, it spews out new chemical elements, deep into space, throwing them across the universe and helping spread entirely new materials to other solar systems.

That process has helped take the universe from the hydrogen, helium and lithium that were present when it began to the rich and varied set of elements that surround us today. Without such dispersal, there would be no life, which is made up of out the more complex and newer elements spread in such violent encounters.

To understand more about that process, the researchers took the tiny grain and analysed it at the atomic level, using highly developed technology. As they did, they discovered just how alien it was, finding huge amounts of a strange carbon isotope known as 13C.

"The carbon isotopic compositions in anything we have ever sampled that came from any planet or body in our solar system varies typically by a factor on the order of 50," said Haenecour. "The 13C we found in LAP-149 is enriched more than 50,000-fold.

"These results provide further laboratory evidence that both carbon- and oxygen-rich grains from novae contributed to the building blocks of our solar system."

The stars that gave birth to the tiny stardust grains will now be long dead. But by studying how they are made up, scietnists can understand the conditions where they came from, the researchers write in the new paper.

"Our find provides us with a glimpse into a process we could never witness on Earth," Haenecour added. "It tells us about how dust grains form and move around inside as they are expelled by the nova. We now know that carbonaceous and silicate dust grains can form in the same nova ejecta, and they get transported across chemically distinct clumps of dust within the ejecta, something that was predicted by models of novae but never found in a specimen."

The scientists are unable to tell exactly how old the grain is, because it is not made up of enough atoms. They hope to find new and bigger pieces to try and understand how they helped lead to the formation of our solar system.

The Independent

More about: solarsystem