On Friday, NASA celebrated a monumental first in its 61 years of history: a spacewalk performed by two women astronauts — without any men suited up alongside them. While it was a much-lauded step for the agency, the milestone also left many wondering why it took so long.

The answer is different depending on who you ask. During the event, one NASA official insinuated that a woman’s physique makes it difficult to perform spacewalks, which is why more men have traditionally done spacewalks. “There are some physical reasons that make it harder sometimes for women to do spacewalks,” Ken Bowersox, the acting associate administrator for human exploration at NASA and a former astronaut, said during a press conference on Friday. “It’s a little bit like playing in the NBA. You know, I’m too short to play in the NBA, and sometimes physical characteristics make a difference in certain activities. And spacewalks are one of those areas where just how your body is built in shape, it makes a difference in how well you can work a suit.”

Others disagree, arguing that height and size don’t matter when you’re in space. In a microgravity environment, the right skills involve meticulous movements and the ability to twist oneself in the proper direction, regardless of physique. The one time a person’s size really does come into play is if they do not have the right suit to accommodate their body.

Spacesuit design has long been biased toward men’s physiques, both due to technological constraints and the fact that NASA preferred male astronauts throughout most of its lifetime. “These repairs and tasks can be performed by anyone in the astronaut corps, that’s for sure,” Dava Newman, the former NASA deputy administrator who is working on a new spacesuit design at MIT, tells The Verge. “That is if they’re in the right suit.”

The spacesuits that astronauts work in today are masterful feats of engineering. In essence, these ensembles are spaceships made in the shape of a human body, providing a tiny bubble of Earth’s atmosphere around a person while in space. “A spacesuit has to basically have all the functionality of a spacecraft with as little excess volume as possible, so the crew member can operate within the suit,” Daniel Burbank, a former astronaut and senior technical fellow at Collins Aerospace, which helped to design the suits on the International Space Station, tells The Verge.

Operating one of these suits is tough. A suit needs to be flexible, so that the person wearing the outfit can move their limbs and do the tasks at hand. But at the same time, a suit must be relatively strong to contain the pressurized gas inside it and protect the wearer from the vacuum of space. Most suits are pressurized to around 4 psi with extra oxygen inside. It’s less than one-third the pressure of sea level here on Earth, about 14.7 psi, which would be impossible to move inside a suit.

But even being able to move against gas pressured to 4 psi does require a certain amount of strength. “We humans cannot operate on a lower pressure,” Pablo de León, professor of space studies at the University of North Dakota, where he specializes in spacesuit technology, tells The Verge. “It’s not like you can say, ‘well I’ll build a spacesuit where you don’t need any physical effort at all and you’ll be able to operate it.’ You just can’t.” However, the strength required to move within a spacesuit is something that every astronaut trains for, regardless of gender. “The training is very rigorous so anyone who’s selected in the astronaut corps has what it takes to perform spacewalks,” says Newman. “The physique is not the issue; they have the capabilities in terms of athletic performance.”

NASA’s Bowersox also suggested on Friday that taller people are somehow more capable of doing spacewalks than others, which is why so few women have done them. “Well, there are some things that, you know, if you look at just statistics, women are probably a little bit smaller than men,” said Bowersox. “It’s a very subtle thing, and you’ll have a larger selection of men with certain amount of strength.” Bowersox also noted that taller people have had easier times during spacewalks, such as repairing the Hubble Space Telescope in orbit around Earth, because they have an easier time reaching around things and getting into crevices. “If you look at some of the Hubble repair missions and things like that, there’s always a tall person or a tall man or two on the crew,” he said.

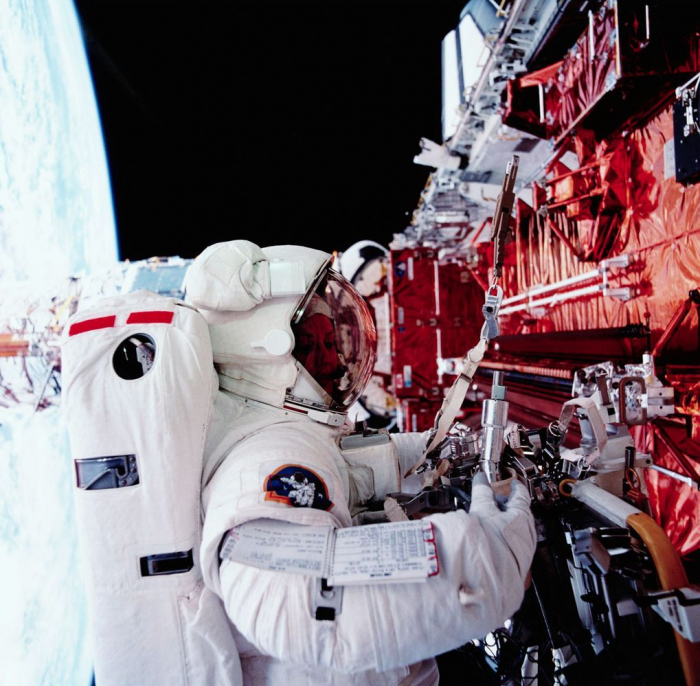

But Newman also disagrees with this assessment, noting there are a wide variety of tasks that need to be accomplished when performing spacewalks, some that are better for smaller people and some that are better for taller ones. “There are a lot of tight places in a Hubble repair, so actually a smaller person has some advantages in terms of getting into some tight spaces and some tight repairs,” says Newman. “Of course, if you need a large arm-length across and that might be, you know, you might want the crew member that has the largest span. So there’s a lot of tasks to do, but definitely universally no one is... disadvantage.” Newman cites the success of former NASA astronaut Kathryn Thornton, for instance, who was the smallest astronaut to repair the Hubble Space Telescope.

Astronaut Kathryn Thornton on a spacewalk to repair the Hubble Space Telescope in 1993 ( Image: NASA)

Perhaps the fundamental flaw that has hindered women’s abilities to perform spacewalks is a lack of suits that fit them. The current spacesuits on board the ISS were designed in the 1970s, and have stayed more or less the same ever since. The nucleus of each suit is an outer shell that fits around a person’s torso, which holds an electronic box that controls all of the suit’s systems. All the other parts — like arms, legs, and backpacks — attach to this shell. And the size of the shell dictates who can wear it.

When NASA was deciding which size torsos to make, the agency opted against creating smalls and even extra-smalls. Last week, Bowersox argued that creating a suit that’s bigger makes it easier to maneuver, however Burbank said that technological limitations of the ‘70s were more to blame. The original design of the suits’ control systems were bulky, and weren’t immediately compatible with a smaller torso. “If you shrink the suit smaller and smaller, you eventually get to the point where that display and control module, which cannot be changed in size, eventually expands across the shoulder width for the crew member,” says Burbank of Collins Aerospace. “So it would have required a fairly significant redesign to accommodate the smallest of the crew members.”

Rather than spend the money to redesign the control module and suits, NASA decided to design the suits bigger — a decision that was made easier by the fact that most of the astronauts at the time were men and probably taller than the average human. The lack of small-sized suits has had repercussions ever since, precluding some women from participating in spacewalks altogether. Despite last week’s milestone, only 15 women have ever performed spacewalks, compared to more than 200 men.

“The astronaut population did look a little bit different back then,” Jessica Meir, who participated in the first all-female spacewalk, said in response to a question from The Verge during a press conference. “I think that when people try to understand why we have the system we have — when you have technology that was developed and hardware that takes a long time to be proven and tested and make its way to spaceflight — sometimes the effects of those decisions made back in the ‘70s carry over for decades to come.”

NASA is trying to fix its past blunders. Last week, the space agency unveiled a new spacesuit that its astronauts will wear if they land on the surface of the Moon. And thanks to more modular sizing and adjustable shoulder bearings, the suit can supposedly accommodate a large range of body types, “from the first percentile female to the 99th percentile male,” according to NASA’s spacesuit designer, Amy Ross. Such a suit will be crucial if NASA plans to land the first woman on the Moon within the next five years, as the agency has repeatedly claimed.

These suits are still your standard air-pressurized suits, which Newman describes as engineering marvels, but still really hard to move in. That’s why she has been researching a new type of spacesuit altogether, one that provides the necessary atmospheric pressure not with air, but by pressing down on the person’s skin. With the right materials and patterns, the suit would adhere to the wearer’s body, compressing the skin and allowing the person to function normally. The technologies needed to turn this concept into reality haven’t been mature up until now, but if Newman can perfect her prototype, she claims she can cut the weight of a spacesuit almost in half, making it easier for many different types of people to wear.

“It’s a different design approach fundamentally. Rather than shrinking spacecraft around someone, it’s saying ‘Oh here’s what the human does and how do we design a suit around the human capabilities?’” says Newman.

While these kinds of suits are still many years away from seeing space, Newman makes the argument that it’s our design choices that matter in the end, as they ultimately influence which people can or cannot do things in space. Blaming a person’s physique or gender is the easy way out. “It’s all an excuse,” says Newman. “Men are definitely not inherently better. We have evidence — it’s a small numbers because we only have a few females — but we have no statistical difference in the performance of astronauts between men and women. We just don’t have very many women because we don’t have many suits that fit them.”

The Verge

More about: spacewalk