There is an art to anger. From a furious Christ pummelling merchants in a 14th-Century fresco by Giotto to a window-smashing spree in Beyoncé’s 2016 music video Hold Up, cultural history is punctuated with punchy images that are more than a little hot under the collar. Such works see wrath and rage not as the shameful antitheses of composure and control but as raw and vital in comprehending who we are. Rarely as celebrated or adored as works devoted to love and affection, these studies in abject aggression are no less profound in their meditation on the full palette of pigments with which we paint ourselves into being. Anger may not be angelic, but it is human and deserves some respect.

For every Klimt Kiss that our hearts know by heart, there is a snarling lip or a tightening knuckle seething in a gallery somewhere, waiting to give us a piece of its mind. But where are these irascible masterpieces and how can we appreciate their aggressive grace? As an eruptive inner energy that consumes our physiques and contorts our faces, anger was slow to show itself in visual art. Even figures traditionally equated with uncontainable fury, such as Euripedes’ (and later Seneca’s) Medea – whose rage so blinds her that she murders her own children in meting out revenge on her husband – seem cool and collected in early representations. In a 1st-Century fresco of the tragic character found in Pompeii, the temperature of Medea’s inner rage is set on the lowest of gentle simmers. Were it not for the dagger that she squeezes in her hand, as she stands coolly beside the children she is about to murder, we might assume Medea is merely lost in an innocent daydream.

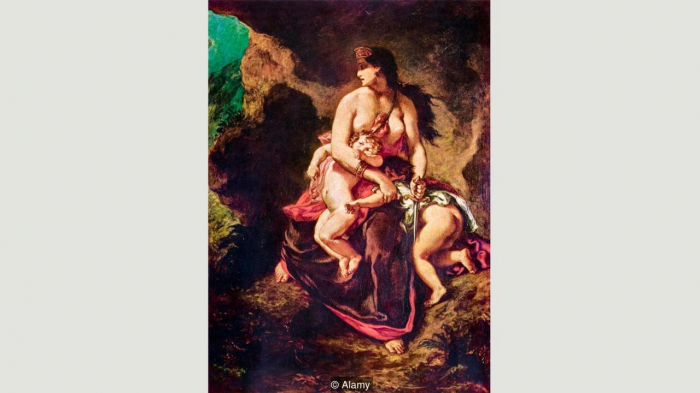

Delacroix’s Medea About to Murder Her Children shows the character from Euripedes’ tragedy taking revenge on her husband for his unfaithfulness (Credit: Alamy)

The fully fuming Medea we’re accustomed to seeing, who wears her hate on her sleeve in portraits such as Eugène Delacroix’s Medea About to Murder Her Children (1838), won’t show her wrathful face for centuries. In the meantime, anger, as a concept, underwent something of a metamorphosis in Western cultural consciousness thanks in part to the theorising of a 4th-Century ascetic monk, Evagrius Ponticus, to whom we owe the notion of ‘deadly sins’. In his treatise Logismoi, written in 375, Evagrius identified eight patterns of evil thought from which sinful behaviour emerges (a schema the Catholic Church went on to abbreviate to seven in the 6th Century) and set anger apart from the other unsavoury emotions of which we’re capable. Evagrius argued that all other sins could be grouped into broader categories: those that stem from lustful desire (including greed, gluttony, and fornication) and those that issue from a corrupt mind (pride and vanity), while sorrow and discouragement together sat somewhere in the middle. But anger was different. It belonged to its own class of ‘irascibility’ or ‘ire’ – a word derived from the ancient linguistic stem ‘eis-’, which carried connotations of divine passion. A close cousin of holy fire, anger was equated by Evagrius to being possessed by a demon and was proof, he concluded, that humans shared a sacred nature with angels.

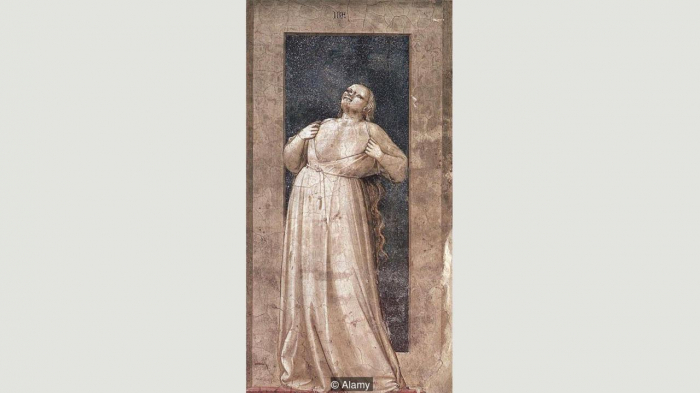

Giotto’s murals of the vices and virtues were done in grisaille – entirely created with grey or a neutral greyish tone (Credit: Alamy)

The influence of Evagrius’s thinking on cultural consciousness is discernible in a seminal depiction of anger in the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua, celebrated for its ethereal fresco cycle by the late medieval Florentine master Giotto. In addition to his famous depictions of lamentations and adorations set against an evaporating blue, Giotto also includes in his design a sequence of 14 personifications of vices and virtues expressed in sober grisaille, or shades of grey and cerebral brown. Among the seven vices he portrays, Giotto’s ‘Ira’, stands out for its intensity. It depicts a woman violently tearing away the material layers that restrict the outward flow of her inner incandescence. The heavenward thrust of the female figure’s exposed chest and the strain of her anguished face to be recognised by the firmament above her, aligns rage with an awkward yearning to commune with something higher. Rage is ugly but it’s real.

Anger isn’t anti-social if it’s righteous and divine

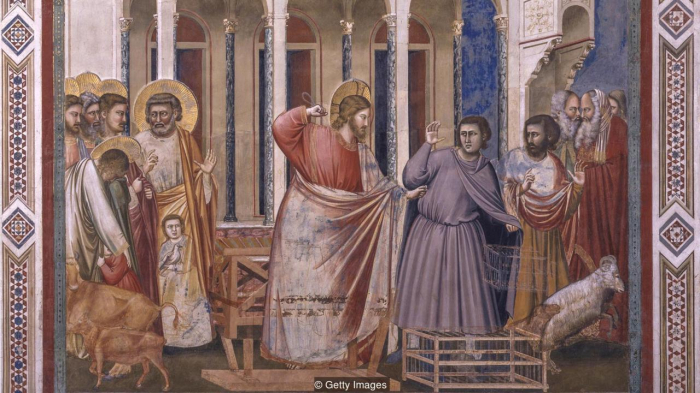

Anyone in any doubt about the artist’s sympathetic attitude to anger needs merely look above the personification of Ira in the chapel to Giotto’s portrayal of Christ punishing a scrum of greedy money changers that he has stumbled across in the temple. Throughout cultural history, the New Testament subject has been a favourite of artists keen to demonstrate that they could capture the human countenance and form in a wider array of moods than merely devotional calm. Tackled by everyone from Pieter Brueghel the Elder to El Greco, the subject allowed painters the opportunity to flex their brushes without appearing to glamorise otherwise unsavoury behaviour. Anger isn’t anti-social if it’s righteous and divine.

Giotto’s fresco cycle at the Scrovegni Chapel was completed around 1305; the murals show the lives of Christ and of the Virgin Mary (Credit: Getty Images)

In almost every version of the incident by Old Masters, Christ is shown with arm raised, wielding ‘a whip of cords’ in faithful conformity to the language of biblical accounts of the story, as he thrashes the merchants who have turned a place of worship into one of worldly profit. But Giotto’s take on the story is striking. At first glance, the outraged Christ appears to go full Fight Club on his target as he dispenses with the swinging lash in favour of bare-fisted justice. “The raising of the right hand, not holding any scourge,” according to a 19th-Century traveller who chronicled every inch of the chapel’s glorious interior, “resembles the action afterwards… of Michelangelo in his Last Judgement”.

For Giotto, anger is an organising energy; everything in his work orbits around the centrifugal force of the juddering fist that is forever about to blow

Look closer, and there may be a slight suggestion of a time-faded whip after all, suspended like a skein of heat vibrating from Christ’s hand-grenade knuckles, which grip our eyes at the centre of the fresco. For Giotto, anger is an organising energy; everything in his work orbits around the centrifugal force of the juddering fist that is forever about to blow. Livestock leap from the imminent blast as a young child, hiding behind a cloak on the left side of the painting, tries desperately to shield from the unfolding violence a white dove, a symbol of tranquil spirit. By serving us anger two ways (both as a vice and a virtue) feet from each other on the same wall of the Scrovegni chapel, Giotto sets the table for all subsequent portrayals of this complex emotion.

Shades of grey

The ensuing centuries saw the emergence of an intriguing tradition of works that seek to understand more fully the nature of rage as an energy that is neither wholly damnable nor divine. From a slapstick allegory of wrath as a tipsy spat between two drunkards in the witty wheel of morality attributed to Hieronymus Bosch, The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things (1505-1510), to the apocalyptic vision The Great Day of His Wrath (1851-3) by the Romantic doomsayer John Martin, the full spectrum of anger is mapped.

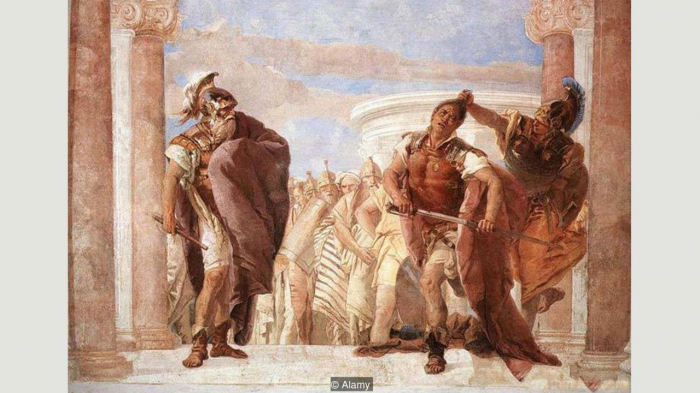

Enraged by the loss of his beloved, Achilles draws his sword to kill Agamemnon – but is stopped by the goddess Minerva, who holds him back by his hair (Credit: Alamy)

Wrath establishes itself as an electric vein that throbs across the forehead of art history – from Giovanni Battista Tiepolo’s suspenseful painting The Anger of Achilles (1757), in which the goddess Minerva stops a seething Achilles from killing Agamemnon by grabbing him by his hair, to the stony rage of John Flaxman’s marble sculpture The Fury of Athamas (1790-94), in which the King of Thebes swings his snatched-up son’s body like a baseball bat.

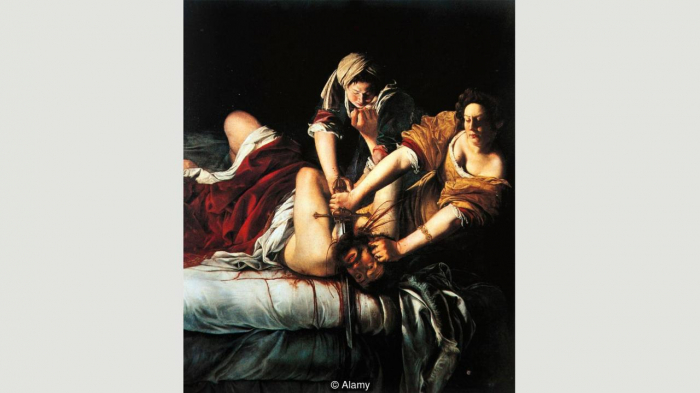

Gentileschi showed Judith decapitating the Assyrian general Holofernes Judith in a graphic, brutal composition (Credit: Alamy)

Crucial to the development of this perennial strand of angry images since the 17th Century has been the unflinching imagination of female artists depicting furious female subjects. Artemisia Gentileschi’s serial fascination both with the biblical story of Judith decapitating the Assyrian general Holofernes, who was about to destroy her home, and with Medea’s infanticide, was followed half a century later by one of the more mesmerising images of composed rage in all of art history – Baroque artist Elisabetta Sirani’s portrait of Timoclea of Thebes (1659).

Timoclea’s story was told by Plutarch; in Sirani’s painting she is exacting revenge on a soldier who raped her (Credit: Alamy)

The only outward sign of inner rage we can detect from Timoclea’s porcelain expression in Sirani’s painting is the slightest angling inward of her eyebrows as she concentrates on the cumbersome task at hand: shoving the bulky body of the Thracian soldier who has just raped her into a well, where she’ll calmly pound him to death with stones. In every respect, Sirani’s study in revenge is a masterclass in poise over provocation, composure over rage. Timoclea’s unflappable control of the farcically flailing legs of her abuser, which she guides into the gap with the finesse of a seasoned forester feeding branches into a woodchipper, vibrates with brutal beauty. She’s angry, but the anger doesn’t consume her. She channels the fire. Unrumpled by rage, her unfailing sense of style (note the cold teardrop pearl pendulating judiciously from her ear, symbolising the suspension of all remorse) continues to resonate in cultural consciousness to this day.

The unflustered cool of Sirani’s portrait of Timoclea finds an unexpected echo in the stylish rampage of Beyoncé’s video Hold Up, in which Beyoncé smashes parked cars with a baseball bat while jauntily singing of love and hatred, commitment and revenge. The flair and frenzy of the video calls to mind a short film from 1997 – Ever is Over All, by the Swiss artist Pipilotti Rist, who calmly saunters down the street shattering one car window after another with an outsized tropical stem that she swings like a surreal cosh. Both Beyoncé’s and Rist’s works seek to reclaim anger as a self-realising energy – a redemptive power, not a destructive disease. In doing so, they tap into a secret well-spring of creative impulse and urgency that is almost as old as art itself.

BBC

More about: art