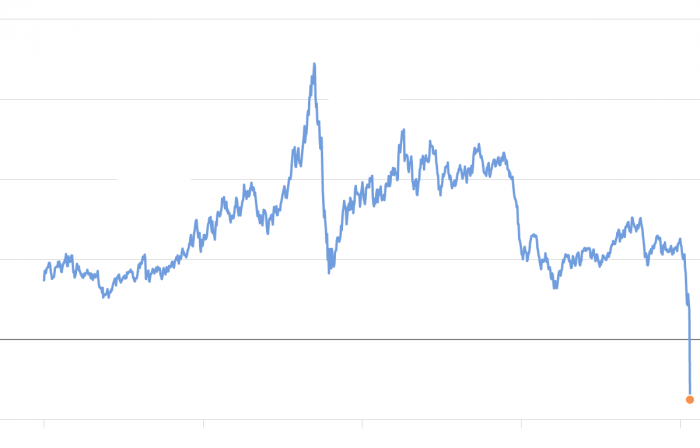

Something bizarre happened in the oil markets on Monday: Prices fell so much that some traders paid buyers to take oil off their hands.

The price of the main U.S. oil benchmark fell more than $50 a barrel to end the day about $30 below zero, the first time oil prices have ever turned negative. Such an eye-popping slide is the result of a quirk in the oil market, but it underscores the industry’s disarray as the coronavirus pandemic decimates the world economy.

Demand for oil is collapsing, and despite a deal by Saudi Arabia, Russia and other nations to cut production, the world is running out of places to put all the oil the industry keeps pumping out — about 100 million barrels a day. At the start of the year, oil sold for over $60 a barrel but by Friday it hit about $20.

Prices went negative — meaning that anyone trying to sell a barrel would have to pay a buyer $30 — in part because of the way oil is traded. Futures contracts that require buyers to take possession of oil in May are expiring on Tuesday, and nobody wanted the oil because there was no place to store it. Contracts for June delivery were still trading for about $22 a barrel, down 16 percent for the day.

“If you are a producer, your market has disappeared and if you don’t have access to storage you are out of luck,” said Aaron Brady, vice president for energy oil market services at IHS Markit, a research and consulting firm. “The system is seizing up.”

Refineries are unwilling to turn oil into gasoline, diesel and other products because so few people are commuting or taking airplane flights, and international trade has slowed sharply. Oil is already being stored on barges and in any nook and cranny companies can find. One of the better parts of the oil business these days is owning storage tankers.

“Traders have sent prices up and down on speculation, hopes, tweets and wishful thinking,” said Louise Dickson, an oil markets analyst at Rystad Energy, a research and consulting firm. “But now reality is sinking in.”

The world has an estimated storage capacity for 6.8 billion barrels, and nearly 60 percent is filled, according to energy experts.

Some of the oil glut is evident in Cushing, Okla., a critical storage hub where the oil that trades on the U.S. futures market is delivered. With a capacity to hold 80 million barrels of oil, Cushing has only 21 million barrels of free storage left, according to Rystad Energy, or less than two days of American production. As recently as February, Cushing was not even up to 50 percent. Now, experts say it will be filled to the brim in May.

Storage is almost completely filled in the Caribbean and South Africa, and Angola, Brazil and Nigeria may run out of warehousing capacity within days.

In his news briefing on Monday, President Trump said the government was “looking to put as much as 75 million barrels” into the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which is used as a buffer during crises and was created after the 1973-1974 oil embargo.

For the first time ever, U.S. oil prices turned negative on Monday and some sellers had to pay buyers to take their fuel.Credit...David Mcnew/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

The reserve has about 635 million barrels of oil, and is equipped to store 75 million barrels more. But the reserve can take only about 500,000 barrels a day.

Congressional Democrats recently balked when the administration proposed spending $3 billion to fill the reserve as part of the stimulus package lawmakers passed last month. But on Monday Representative Lizzie Fletcher, a Houston Democrat, said she would introduce legislation appropriating funds for a reserve purchase.

But it will be hard to quickly fix the oil industry’s problems. The oil infrastructure is complicated and it’s not easy to turn off the taps. In addition, countries like Saudi Arabia and Russia, whose economies are reliant on oil, only reluctantly cut production.

Shutting down oil wells and then restarting them when demand returns can require expensive manpower and equipment. Fields do not always recover their former production. In addition, some oil companies keep pumping, even if they are losing money, in order to pay interest on their debts and stay alive.

The huge drop in prices on Monday was exaggerated by the way oil prices are set.

When traders sell oil they guarantee delivery at a future time. Normally the price differences between oil for next month and the following one are relatively minor. But on Monday oil to be delivered next month, or May, was essentially deemed worthless. Oil set for delivery in June also fell but not nearly as much — more reflective of the market’s view on the current value of crude.

Brent crude, the oil price benchmark outside the United States used by much of the world, whose May contract has already expired, fell about 5 percent to a little under $27 a barrel.

The disparities showed a market “undergoing extreme stress,” said Antoine Halff, a founding partner of Kayrros, a research firm. “It’s a sign of the very real imbalance between supply and demand.”

A little over a week ago, there was some optimism in the oil industry. The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, Russia and other producers said they would cut 9.7 million barrels a day of production, or about 10 percent of global oil output, the largest cut ever. It was a grim acknowledgment that global demand had collapsed.

But that record cut will not be nearly enough. Analysts expect daily oil consumption to fall by as much as 29 million barrels in April, about three times the cuts pledged by OPEC and its allies, and May isn’t expected to be much different.

“It’s relatively impressive in terms of the overall number, but it’s not enough to tighten the market between now and the fourth quarter of 2020,” David Fyfe, chief economist at Argus Media, a commodities pricing firm, said about the cut by OPEC and its partners.

U.S. oil producers are also reducing production, but not rapidly enough. At the current pace, American production will decline to less than 11 million barrels a day by the end of the year, from 13.3 million barrels a day at the end of 2019.

Many companies are already reporting substantial losses, and experts said businesses across the oil patch will have to seek bankruptcy protection in the coming months.

Halliburton, the giant provider of equipment, workers and services to oil companies, on Monday reported a $1 billion loss in the first quarter, in contrast to net income of $152 million in the same period a year earlier.

Companies have filled up about 60 percent of the oil storage in the world as demand for energy has collapsed.Credit...Edgard Garrido/Reuters

Gary Ross, chief executive of Black Gold investors, an oil trading firm, said demand was falling so fast that U.S. companies that recently were exporting oil are now cutting production.

“It doesn’t matter whether it is $15, $10 or $8, you are still going to” stop production, Mr. Ross said. ConocoPhillips, one of the largest U.S. oil companies, said last Thursday that it would temporarily curtail about 225,000 barrels a day of production.

Such cuts should help stabilize the markets, but it might take months. The U.S. contract for oil delivered in May 2021 was trading on Monday at about $35 a barrel, hinting at how long it might take for prices to reach levels they were at just a few weeks ago.

The oil industry’s plight is forcing policymakers to consider intervening more forcefully.

And on Tuesday, the Texas Railroad Commission, which regulates oil and gas drilling, will take up a proposal for a 20 percent statewide production cut on Tuesday. The commission used to regularly manage oil production but hasn’t done so since the early 1970s.

Exxon Mobil and other large companies have opposed mandated cuts but some smaller companies want the commission to act.

Scott Sheffield, chief executive of Pioneer Natural Resources, told the commission at a hearing last week that if the oil price stayed around $20 a barrel for a while, 80 percent of the hundreds of independent oil companies in the state would be forced into bankruptcy and 250,000 workers would lose their jobs.

At $30 a barrel, many companies would be “crippled,” Mr. Sheffield said. “But at least the industry will survive.”

Stanley Reed, a London-based journalist, has been writing for The New York Times on energy, the environment, and the Middle East since 2012. Before that he was London bureau chief for BusinessWeek magazine.

Clifford Krauss is a national energy business correspondent based in Houston. He was previously the bureau chief of The New York Times's Buenos Aires and Toronto bureaus, and has reported in recent years from North Africa and the Middle East. In 2016, he shared the Society of Publishers in Asia Award for explanatory reporting.

Read the original article on the New York Times.

More about: oilprices