What do the greatest paintings and sculptures in cultural history – from Girl with a Pearl Earring to Picasso’s Guernica, from the Terracotta Army to Edvard Munch’s The Scream – have in common? Each is hardwired with an underappreciated, indeed often overlooked, detail that ignites its meaning from deep inside. That, at least, is the premise of my book, A New Way of Seeing: The History of Art in 57 Works, a study that invites readers to reconnect with works that are so familiar we no longer really see them.

Taking as my starting point the most revered images in all of human history (from Trajan’s Column to American Gothic, the Elgin Marbles to Matisse’s The Dance), I went looking for what makes great art great – why some works continue to vibrate in popular imagination century after century, while the vast majority of artistic creations slip our consciousness almost as quickly as we encounter them. Combing the surface of these works, I was surprised to discover that each contains a flourish of strangeness which, once spotted, unlocks exciting new readings and changes forever the way we engage with these masterpieces.

As these remarkable details began to reveal themselves, from a ghostly finger fidgeting on Mona Lisa’s right hand to a tarot symbol for fortitude hiding in plain sight in one of Frida Kahlo’s most mysterious self-portraits, I was reminded of a remark by Charles Baudelaire. “Beauty,” the French poet and critic wrote in 1859, “always contains a touch of strangeness, of simple, unpremeditated and unconscious strangeness.”

What follows is a brief digest of some of the more extraordinary details – touches of strangeness that invigorate, often subliminally, many of the most recognisable images in art history.

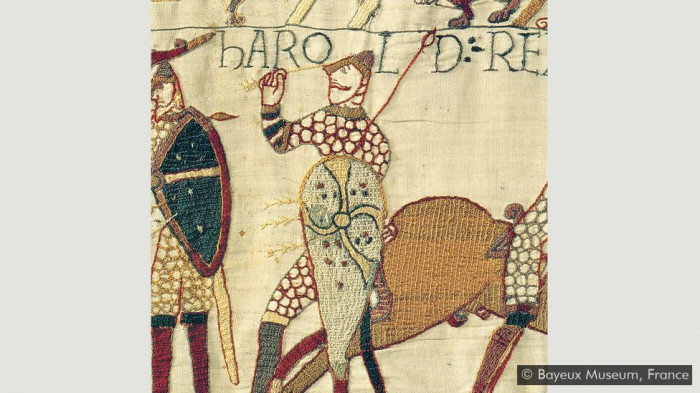

(Credit: Bayeux Museum, France)

The Bayeux Tapestry (c. 1077 or after)

The forgotten women who, a millennium ago, embroidered the 70m of cloth on which the Bayeux Tapestry chronicles the events that led to the Norman Conquest, were not just exquisite seamstresses, they were exceptional storytellers. The arrow that pierces the eye of King Harold in a climactic scene near the end of the visual epic is a meta-narrative device that doubles as the very needle with which the history has been intricately woven. By grabbing the arrow, the wounded Harold blurs his own identity into those of both the artist and the observer, whose own eye has been pulled forward, scene by scene. With a single stitch, our eye, Harold’s, and that of the seamstress’s needle collapse into one.

(Credit: Uffizi, Florence)

Sandro Botticelli, The Birth of Venus (1482-5)

A wind-spun spiral of golden hair suspended on the goddess’s right shoulder in Sandro Botticelli’s Renaissance masterpiece The Birth of Venus whirs like a miniature motor on the vertical axis of the painting, propelling it forward into our imagination. A perfect logarithmic curl, this is no incidental ornament or accident of brushwork. The same spinning vector, observable in the plunge of raptor birds and the twist of nautilus shells, has hypnotised thinkers since antiquity. In the 17th Century, a Swiss mathematician, Jacob Bernoulli, would eventually christen the curl spira mirabilis, or “marvellous spiral”. In Botticelli’s painting – a work that celebrates timeless elegance – the inscrutable spiral whispers into Venus’s right ear, divulging to her the very secrets of truth and beauty.

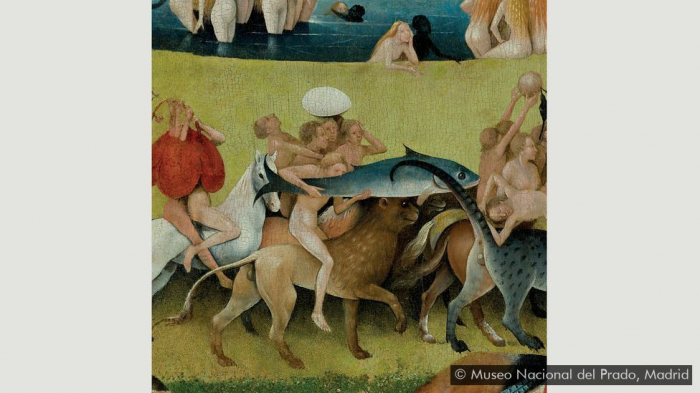

(Credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid)

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights (1505-10)

That an egg lies hidden in plain sight at the dead centre of Hieronymus Bosch’s carnival of fleshly shenanigans (balanced atop a horseman’s head) is well enough known by critics and casual admirers of the painting alike. But how does that delicate detail unlock the work’s truest meaning? If we swing shut the triptych’s side panels to reveal the work’s outer shell and the ghostly ovoid of a fragile world that Bosch has depicted on the work’s exterior – a translucent orb floating in the ether – we discover that he conceived his painting as a kind of egg endlessly to be cracked and uncracked every time we engage with the complex work. By opening and closing Bosch’s painting, we alternately set a fledgling world in motion or turn the hand of time back to before the beginning, before our innocence was lost.

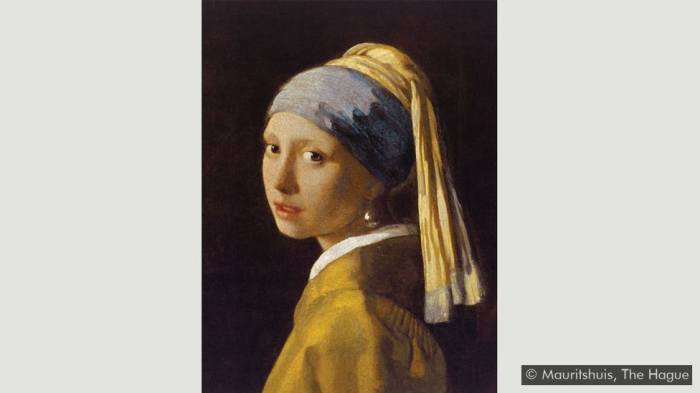

(Credit: Mauritshuis, The Hague)

Johannes Vermeer, Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665)

Think you see a pearl dangling lustrously in Vermeer’s famous portrait of a girl endlessly turning towards or away from us? Think again. The swollen bauble around which the painting’s mystery spins is just a pigment of your imagination. With a flick of the wrist and two deft dabs of white paint, the artist has tricked the primary visual cortices of our brains’ occipital lobes into magicking a pearl from the thinnest of air. Squint as tight as you wish and there is no loop that links the ornament to her ear. Its very sphericity is a hoax. We’ve willed the earring into weightless suspension from the puniest of white apostrophes. Vermeer’s precious gem is an opulent optical illusion, one that reflects back on our own illusory presence in the world.

(Credit: National Gallery, London)

JMW Turner, Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway (1844)

It’s no secret that Turner secreted a sprinting hare in the murky path of the approaching locomotive. The artist himself pointed it out to a little boy who visited the Royal Academy on varnishing day just as the work was about to go on show. But how does this tiny detail ignite the meaning of Turner’s huge meditation on encroaching technology? Why did he feel compelled to point it out? Since antiquity the hare has symbolised rebirth and hope. The emotions of visitors who saw the painting when it was first exhibited in 1844 were still raw with the horror of a tragedy that had occurred on Christmas Eve two and a half years earlier, when a train derailed 10 miles from the bridge depicted in the painting – an accident that killed nine third-class commuters and maimed another 16. By going small in the emblem of the hare, an artist famous for going big transforms his painting into a poignant tribute and meditation on the fragility of life.

(Credit: National Gallery, London)

Georges Seurat, Bathers at Asnières (1884)

The large painting of Parisians whiling away a lazy lunch hour on the banks of the river Seine, the first work ever exhibited by Seurat, was initially finished in 1884. It was then touched up by the artist years later, after he had begun to perfect his signature technique of applying small distinct dots that cohere in the eye of the observer when seen at a distance. The colour theory that underpins Seurat’s more mature pointillist style owes its origin in part to the ideas of a French chemist, Michel Eugène Chevreul, who explained how the juxtaposition of hues can generate a persistence of tone in our imagination. In the hazy distance of Seurat’s painting, a row of smokestacks rise from a factory that produced candles according to an industrial innovation for which Chevreul was also responsible. These chimneys, which seem more like paintbrushes daubing the work into existence, are a tribute to the thinker without whom Seurat’s resplendent vision would not have been possible.

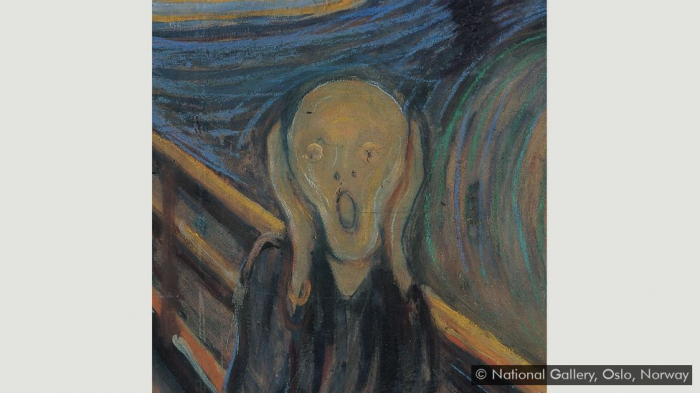

(Credit: National Gallery, Oslo, Norway)

Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893)

It has long been assumed that the howling figure in Edvard Munch’s The Scream – an archetype of angst that still flickers above the popular imagination more than a century after it was created – was indebted chiefly to the aghast expression frozen on the face of a Peruvian mummy that the artist encountered at the 1889 Universal Exposition in Paris. But Munch was an artist concerned more about the future than the past, and especially anxious about the pace of technology. Surely he would have been even more deeply impressed by the breath-taking spectacle of an enormous lightbulb filled with 20,000 smaller bulbs that stood on a pedestal and towered over the pavilion in the same Exposition? A tribute to the ideas of Thomas Edison, the sculpture rose like a crystalline god heralding a new idolatry, flipping a switch in Munch’s mind. The contours of The Scream’s yowling face reflect with extraordinary precision the drooping jaw and bulbous cranium of Edison’s terrifying electric totem.

(Credit: Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna)

Gustav Klimt, The Kiss (1907)

Surely love and passion stand at the furthest extreme from the long white lab coats and microscopic slides of scientific testing. Not according to Gustav Klimt’s painting The Kiss. The year he painted his work, Vienna was alive with the language of platelets and blood cells, especially around the University of Vienna where Klimt himself had, years earlier, been invited to create paintings based on medical themes. Karl Landsteiner, a pioneering immunologist at the University (the scientist who first distinguished blood groups) was hard at work attempting to make blood transfusions succeed. Look closer at the curious patterns that throb on the woman’s frock in Klimt’s painting and one suddenly sees them for what they are: Petri dishes pulsing with cells as if the artist has offered us a scan of her soul. The Kiss is Klimt’s luminous biopsy of eternal love.

BBC Culture

More about: art

-1743409918.jpg&h=190&w=280&zc=1&q=100)