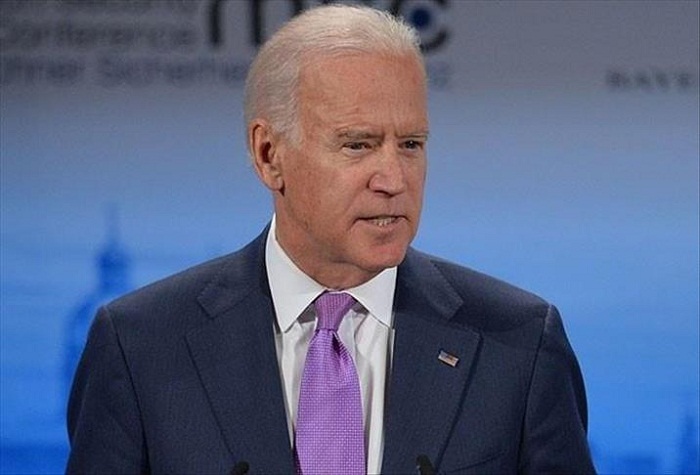

With the Taliban’s sudden reconquest of Afghanistan, US President Joe Biden is learning how quickly “inbox problems” can derail other objectives. Whether he will recover and salvage his legislative agenda remains to be seen; history offers conflicting lessons.

A political leader’s performance and legacy are usually defined more by how he handles his inbox than by whether he delivers on hyperbolic campaign promises or visions of the promised land. US President Joe Biden is learning this lesson during his first summer on the job. Reality is rudely intruding on his plans.

Many “inbox problems” arrive unexpectedly, as was true of the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks or the COVID-19 pandemic; but others are more easily anticipated, as in the case of persistent inflation and long wars. Biden’s problems this summer fall into the latter category. His radical economic agenda has predictably exposed rifts among congressional Democrats and increased the risk that centrist and independent voters will experience buyer’s remorse. Democrats are now rightly worried that the Republicans will retake the House of Representatives in the 2022 midterm elections.

There is time for Biden to recover, of course. But his honeymoon has clearly ended with the disastrous decision to withdraw the last US forces from Afghanistan without a plan for safely evacuating Americans, allies, and the thousands of Afghans who risked their lives supporting US-led operations there.

Biden ignored the advice of military leaders and diplomats who argued for maintaining a small residual force to provide intelligence and air support to the Afghan army, which had provided stability for a year and a half without a single US combat death. Nor did Biden bother to consult the NATO allies whose forces on the ground far outnumbered the small remaining US contingent.

Democrats are hoping the Afghan debacle will be less salient to voters by November 2022. But the fall of Kabul could have a lasting effect by reinforcing the notion that Biden and his advisers are weak and not up to the job of dealing with a dangerous world. It also may threaten the administration’s economic policy agenda.

The far left of the Democratic Party is demanding that the $1 trillion bipartisan infrastructure bill already adopted by the Senate be held hostage to secure passage of a massive, radical $3.5 trillion redistribution bill loaded with permanent new entitlements with no work requirement. The party’s few centrists are understandably balking.

But the legislative fight is not Biden’s only source of economic woe. Inflation has taken a sharp upward turn, with the core consumer price index having risen by over 4.3% in the last 12 months (through July) – a level that in 1971 caused a conservative president, Richard Nixon, to impose distortionary wage and price controls. Moreover, the measure for core inflation strips out volatile food and energy prices, which are rising even faster and doubtless will be weighing on budget-minded voters.

True, some of today’s high inflation reflects the bounce-back from last year’s depressed prices, and some stems from “temporary” supply-chain disruptions (for example, semiconductor shortages have hindered auto production). But if the US Federal Reserve finds that it must contend with inflation risks sooner than it expected, the interest cost on Biden’s massive deficits (along with the big deficits built up by Donald Trump and Barack Obama) will soar, quickly rendering his expensive domestic spending agenda unsustainable.

Worse yet, the coronavirus’s Delta variant is running rampant, and vaccinations are lagging behind the administration’s predictions (despite massive spending and daily presidential exhortations). Taken together, these factors all threaten to slow the strong economic recovery that Biden inherited.

The administration’s performance on other issues has been equally inept. After restricting domestic energy production in a poorly considered attempt to hasten the transition from fossil fuels to “clean” energy, it recently found itself in the awkward position of having to urge OPEC to pump more oil.

The risks of curtailing fossil-fuel production should have been obvious: Germany still uses lots of lignite (the dirtiest form of coal) to deal with soaring costs and a stressed electricity grid; and California, the state “leading” the transition, finds itself gigawatts short of peak energy needs, with rolling blackouts likely for the foreseeable future. Biden has also made way for the completion of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, which will make Europe even more dependent on Russian gas.

At the same time, Biden’s loosening of some Trump-era immigration and border policies has encouraged a record flow of migrants to travel from dozens of countries to the southern border. Local charities, hospitals, and communities are overwhelmed, and many illegal immigrants reportedly have been released into the United States even after testing positive for COVID-19.

Governing isn’t easy in large, diverse, and complex societies. It involves choices and tradeoffs that are not universally popular. But after running explicitly on the promise of restoring normalcy and moderation, Biden’s administration has so far proved incompetent and inept.

Former Secretary of Defense and CIA Director Leon Panetta has likened the Taliban’s reconquest of Afghanistan to John F. Kennedy’s Bay of Pigs fiasco. But a better analogy is to US President Jimmy Carter’s flailing attempt to rescue Americans held hostage in Tehran in 1979. Carter never recovered politically, but Kennedy did. He went on to orchestrate an end to the Cuban Missile Crisis, with an agreement to get Soviet missiles out of Cuba in exchange for the US removing missiles from Turkey.

Can Biden recover from this summer’s fiascos and salvage his economic agenda? Will his perceived weakness lead to additional foreign crises that sap resources and attention? History offers conflicting lessons. When President Ronald Reagan inherited record-breaking inflation from the hapless Carter, he backed Fed Chair Paul Volcker’s inflation-fighting efforts. The resulting recession doomed his party in the 1982 midterm elections. But a strong recovery thereafter positioned him for a huge re-election win and subsequent legislative victories, including the landmark 1986 tax reform.

Trump, who in 2019 had a clear shot at re-election, was derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting recession despite the success of Operation Warp Speed, his program to facilitate the development of effective vaccines. At the rate Biden is going, he could fare even worse.

Michael J. Boskin is Professor of Economics at Stanford University and Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution. He was Chairman of George H.W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers from 1989 to 1993, and headed the so-called Boskin Commission, a congressional advisory body that highlighted errors in official US inflation estimates.

More about: