Granted, there is a lot about the movie that’s annoying. After two-and-a-half hours of Alan Silvestri’s piano-tinkling score, I too feel like banging my head against the nearest wall. And I’m certainly not going to win any cool points defending a film that inspired a shrimp restaurant chain. But every time Gump pops up on TV I get sucked in. No matter which point in the plot I enter from – Forrest as a child teaching Elvis how to swivel his hips, Forrest as a Vietnam vet showing the scar on his “butt-ox” to LBJ in the White House – I inevitably find myself curled up on the sofa with a bowl of popcorn in my lap. Which, in my opinion, is the definition of a really good film.

Pulp Fiction, which Gump beat for best picture at the 1995 Oscars (along with The Shawshank Redemption, Quiz Show and Four Weddings and a Funeral) gets all the credit for daring cinematic experimentation, with its zigzagging chronology and script full of pop culture shout-outs.But Gump is every bit as unconventional as Pulp Fiction. Eric Roth’s screenplay ignores all the formulas of film-making, and the movie unfolds more like a modern novel than a motion picture. It’s a film with no villains; no central conflict and no over-arching narrative tension. It’s not a comedy, and it’s not a drama, and it’s not any other genre you can pin down. Its hero is a man with an IQ of 75 who wanders through the second half of the 20th Century randomly bumping into one historical event after another – standing next to George Wallace at the schoolhouse door in Alabama in the 1950s, getting swept onto a podium with Abbie Hoffman at an anti-war protest in the 1960s, striking it rich by investing in “a fruit company” called Apple in the 1970s — emerging in the final reel as the wisest, least cynical person on the screen.

Of course, part of what makes the movie so easy to watch is Tom Hanks. Many great actors have played developmentally challenged characters over the years, with varying degrees of success. Peter Sellers’ turn in 1979’s Being There was extraordinary in its own way, but he played Chauncey Gardner as such a blank slate you could never quite tell what he was thinking. Sean Penn perhaps went too far in 2001’s I Am Sam, and was punished for it by critics and audiences alike. But Hanks, with his stiff-as-a-board posture and sing-song southern accent, gave Gump a charm and empathy and depth of humanity – there isn’t a moment when you don’t know exactly what’s going on in Gump’s head – that made audiences want to give the character a hug.

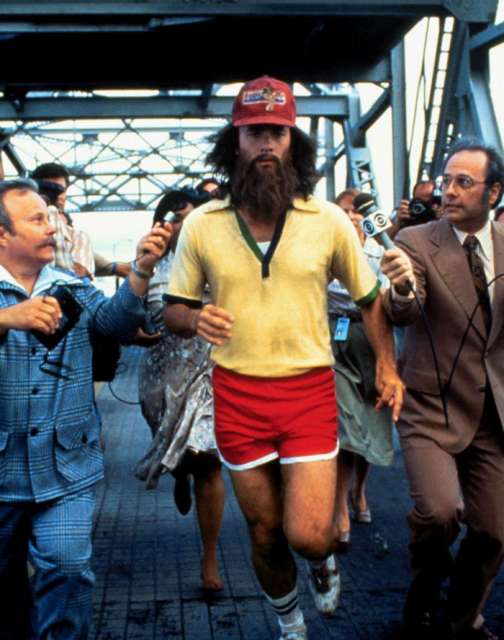

At the time of its release, its big gimmick was the special effect of digitally inserting Gump into vintage newsreels and other historical footage. Robert Zemeckis wasn’t the first director to perform this cinematic slight of hand – Woody Allen photo-bombed Adolf Hitler at the Nuremberg Rally in 1983’s Zelig – but nobody had ever done it quite so seamlessly, or with so much heart.

The scene when Gump accidentally provides John Lennon with the lyrics to Imagine while they’re both appearing onThe Dick Cavett Show? It’s not just a CGI sight gag – it’s among the most poignant moments of the film. In fact, the effects in Gump are so fresh and eye-catching, it’s easy to overlook the movie’s other stunning visual asset: Don Burgess’s cinematography. The shot towards the end, of Robin Wright kneeling on the earth in front of the shack in Alabama where her character grew up with an abusive father, is so heartbreakingly gorgeous, you very nearly forget what a vile person Jenny is through most of the film.

I’m not saying Gump is a perfect movie. I’m not even saying it necessarily deserved to win best picture. But there’s no denying it connects emotionally in a way the hipper, flashier Pulp Fiction never could. It invented a totally new pop cultural archetype – a simpleton with Zen-like wisdom and the gift of historical serendipity – that continues to resonate today. Twenty-one years after its release, the film is still touching audiences, still being quoted (“Stupid is as stupid does”), still irritating critics.

All I am saying is that next time it turns up on television, I’m pretty sure I’ll be popping corn.

Why I hate Forrest Gump

Around the World in 80 Days. The Greatest Show on Earth. Chariots of Fire. Any amateur Oscar historian can reel off a list of the Academy`s greatest misses – movies remembered, when they are at all, only as examples of how rarely the winner of best picture holds any real claim on the term. Forrest Gump deserves a place among their ignoble ranks, to be classed with the all-time "What were they thinking?" moments in Oscar history. As bad as its victory over Pulp Fiction seemed in 1994, it looks worse now, its success both with the Academy and at the box office not only galling but outright baffling.

I owe my career as a critic, at least in part, to Forrest Gump. In the summer of 1994, I was heading towards my last year as a university student, an aspiring critic who`d never written for an audience larger than an English class. But when I saw the film, I had to write about it. I petitioned the editors of the school newspaper to let me review movies for them, hoping against hope that Gump would play on campus and I`d get my chance. The review, just over 1,000 words of supercilious vituperation, fortunately predates the era when every last word was archived online. But it did garner me my first piece of hate mail: proof that I was now a critic.

Looking at Forrest Gump today, it isn`t as bad as I remembered – it’s worse. At 21, full of the ideological certitude instilled by a pricey liberal-arts education, my complaints were largely about the movie`s flipbook approach to history, the way it exalted an uncommitted simpleton and slandered the political movements of the 1960s, how it paved the path to a white man`s enlightenment with the dead bodies of women and black people. Now, at twice that age, I`m more viscerally repelled by its smug, airless aesthetics, Tom Hanks`s insufferable, tic-ridden performance (especially hard to stomach after his career-best work in Captain Phillips), director Robert Zemeckis`s penchant for staging historical periods like grade-school dioramas.

In retrospect, Forrest Gump seems like a precursor to the lifeless motion-capture movies (The Polar Express, Beowulf, A Christmas Carol) Zemeckis would squander the entire first decade of the new millennium on — perhaps as close as a major film-maker has ever come to being ruined by technology. And Gump marked the moment the age of digital effects came into full flower. Jurassic Park, released the previous summer, used a handful of CGI dinosaurs to great effect, but Zemeckis used digital from the movie`s first shot to its last, sending a feather scudding from high above the earth to land by Hanks`s feet and allowing Gary Sinise to play a Vietnam veteran who loses both legs in the war.

Gump was a massive box office success, grossing $677 million worldwide – adjusted for inflation, it was more successful than The Dark Knight in the US (Credit: Af Archive/Alamy)

Zemeckis and his technicians were so preoccupied with whether they could make the movie`s effects work they didn`t stop to wonder if they should. What purpose does it serve to insert Hanks into newsreel footage of JFK so that the leader of the free world can chuckle when Forrest tells him "I need to pee," or so that LBJ can request a peek at his “butt-ox” wound? Who could ever have thought a scene where Forrest appears on the Dick Cavett Show and, in describing his trip to Communist China, inadvertently gives John Lennon the idea for Imagine, was a good idea, or even a tolerable one? ("No possessions?" asks the cut-rate impersonator employed to mimic Lennon`s voice. "No religion, too?")

Its abject moral idiocy forestalls any attempt at extracting a coherent ideology.

Although the movie`s depiction of Black Panthers as sloganeering windbags and the anti-war protestors of Students for a Democratic Society as woman-slapping brutes did get Forrest Gump drafted into the culture wars – Republican Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich called it "a reaffirmation that the counterculture destroys human beings and basic values," and the National Review awarded it "Best Picture Indicting the Sixties Counterculture" – its abject moral idiocy forestalls any attempt at extracting a coherent ideology. When Forrest`s ancestor dons a Ku Klux Klan hood and essentially rides into DW Griffith`s notoriously racist The Birth of a Nation, it`s no comment on history, just a nifty trick. One can only thank whatever gods one might pray to that the original sequence, in which Forrest`s ancestor gets covered in mud and is inadvertently lynched, was cut from the production for time.

Hanks was honoured with a best actor Oscar and Sinise received a nomination for supporting actor, but Robin Wright should have been recognised for the grace with which she bears the many torments the movie dumps on her character. As a child, Jenny is beaten and, it`s implied, sexually abused by her father; as an adult, she drifts through the decades, shooting heroin and snorting cocaine while feckless, virginal Forrest stumbles into one gold mine after another. The movie pities her, but it never suggests we might empathise with her, and it ends by slut-shaming her into an early grave. Forrest just keeps running.

Forrest Gump feels like an attempt to recapture the innocence and playfulness of an earlier time, but it`s not nostalgic for the past; it`s nostalgic for old movies. Zemeckis is a consummate technician, which has served him well, from Back to the Future to What Lies Beneath, but he can`t muster the sincerity of John Ford or the grace of Powell and Pressburger, to name just two of Gump`s would-be antecedents. The movie wants to be as light as its famous feather, but it tromps through history like a clumsy magician, one who can`t wait to show you how the trick is done.