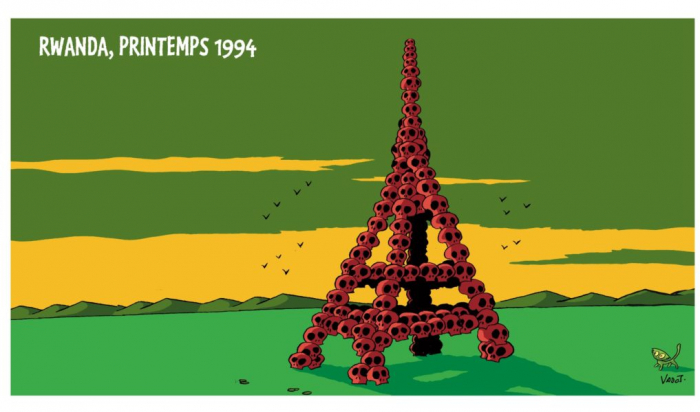

The Rwandan genocide is considered one of the black stains of France’s history. The tragedy that happened in the late 20th century testifies to the fact that the inhuman actions of countries like France are not a thing of the past and continue to be observed even today.

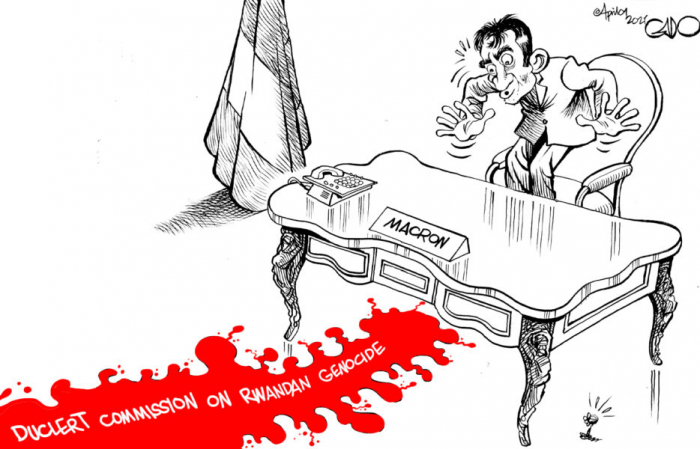

On 7 April 2019, President Emmanuel Macron announced the establishment of a special commission tasked with investigating France’s role in the Rwandan genocide. After the commission submitted its findings to Macron on 26 March 2021, the French president was to apologize for his country’s role in the genocide of the Tutsi. He also admitted that France actually backed the genocide by ignoring the massacre warnings.

France’s role in the tragic events in Rwanda in the early 1990s triggered controversy and tension between Paris and Kigali for nearly three decades. The refusal to remove the seal of secrecy from the archival documents of that time is said to be a major obstacle to uncovering the truth.

Failure to fully open archives

In April 2019 - 25 years after the tragic events in Rwanda, Macron announced the establishment of a special commission to probe the “black stains” in Paris’ policy towards Rwanda. The commission, headed by French historian Vincent Duclair, was granted access to all the archives of France.

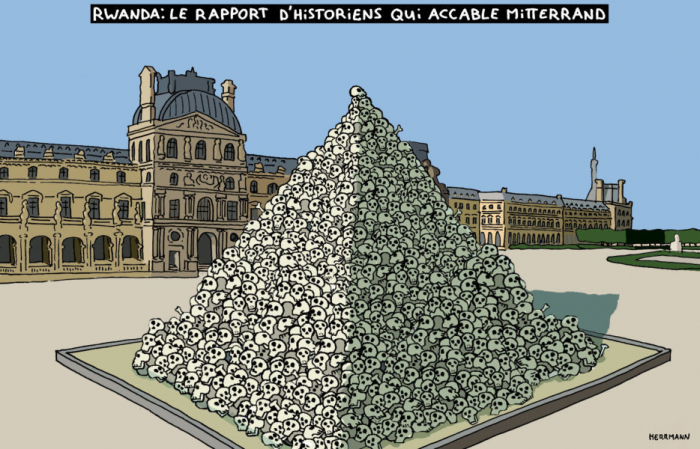

After two years of work by dozens of historians, a report was prepared based on 8,000 documents, manuscripts, diplomatic letters and telegrams, analytical notes, protocols of defense council meetings, and other archival sources. As Macron promised, the commission had access to the secret archives of the Foreign Ministry, the Defense Ministry, and the External Documentation and Counterespionage Service (SDECE), as well as the personal archive of President François Mitterrand.

Despite all this, numerous documents necessary for the disclosure of the events remained unstudied. The parliamentary commission on the Rwanda genocide of 1998 denied the request by historians to share the relevant materials. It was impossible to get access to the archive of Jean-Christophe Mitterrand (the son of former French president François Mitterrand was an advisor on African affairs until July 1992). The Legion of Honor also declined numerous requests by the commission. Moreover, SDECE did not fully declassify its archives.

The 1,200-page final report submitted to Macron emphasizes that its authors refuse to act as judges who blame the people involved in the perpetration of the genocide. The document concludes that the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda must identify and punish those guilty of the genocide. The commission was only tasked with probing France’s role in the Rwandan genocide with the help of a limited number of documents.

France’s role in the Rwandan genocide was also investigated by a special parliamentary commission set up by the then Minister of Defense Paul Quilès. However, historians claim that Paul Quilès had “neither the real capacity nor the great desire” to uncover the truth.

France’s bloody intentions

At the Africa-France summit in 1990, France's Socialist president François Mitterrand called on the leaders of African countries for democratic changes. The speech made by François Mitterrand at the summit is considered to be a turning point in French-African relations. In the following years, the Elysée Palace reviewed its relations with Rwanda in this context. Juvénal Habyarimana, a Hutu representative who was in power at that time, assured France that they were ready for demographic changes.

In 1990, Tutsi rebels from Rwanda's neighboring Uganda formed the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) and launched a struggle to overthrow the Habyarimana government. Given the fact that Paris considered the RPF to be a tool serving British interests, therefore, it turned a blind eye to the violence of the Habyarimana regime against Tutsi rebels.

State market

One of the chapters of the report deals with the problems of state institutions during Mitterrand’s presidency. It stresses that many issues have been solved without taking into account the decisions of the relevant ministries and departments. There were systematic deviations from the rules of government decision-making. Mitterrand's military advisers, especially General Jean-Pierre Huchon, who was in constant contact with the officials charged with relations with Rwanda, mainly contributed to the “Rwanda dossier”. These contacts were often made through informal channels. Instructions were given verbally, when written, the received message was required to be destroyed immediately. Experts have confirmed that this kind of practice is abnormal.

The report also cited Colonel Galie, the military attache at the French Embassy in Kigali, as saying: “The authorities of neighboring Uganda masterminded the RPF attack. Such an approach was supposed to help legitimize France’s intervention before the international community.”

All this resulted in the approval by Mitterrand of his private military staff as a decision-making center for Rwanda. However, some officials voiced their objection to this decision. For example, the then-defensive minister Pierre Joxe proposed President Mitterrand change the practice of non-transparency of verbal instructions and lack of political and administrative responsibility. However, his proposal remained unanswered.

Culmination

On 6 April 1994, President Habyarimana’s plane was shot down by a missile while approaching Kigali. Those close to the president immediately blamed the terrorist attack on the RFP insurgents. The news of a terrorist attack signaled the start of massacres against Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Three days after the assassination of Habyarimana, on April 9, the interim government of Rwanda, dominated by Hutu radicals, was established at the French Embassy in Kigali. Two days later, on April 11, Ambassador Marlaud asked Paris to evacuate French citizens and the embassy staff from Kigali. In those days, mass murders, rapes, and tortures were taking place against Tutsis and Hutus all over the country.

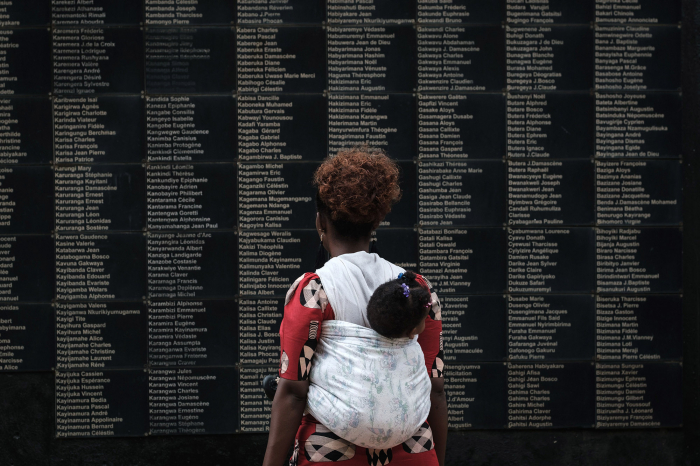

Only on May 18, French Foreign Minister Alain Juppé announced that an act of genocide was committed by the Rwandan government against the Tutsis. Opération Turquoise, a French-led military operation intended to protect civilians on both parties to the conflict, was planned to be launched on June 22. By this time, about 800,000 Rwandans, most of whom were representatives of the Tutsi people, became victims of the genocide that lasted for 100 days.

Conclusion

France has long supported a regime that promoted racist crimes. France has turned a blind eye to the preparation of the most radical elements of this regime for genocide. During the genocide, this country did not rush to break relations with the provisional government that carried it out. Although it was possible to save the lives of most of the Tutsis who were exterminated in the first weeks in Rwanda, the operation was delayed.

France’s role in the Tutsi genocide has long soured relations between Paris and Kigali. From 2006 to 2009, the countries even severed diplomatic ties. In 2014, Paul Kagame, the incumbent Rwandan president and founder of the Rwandan Patriotic Front, stated that “France played a direct role in the perpetration of the genocide.”

AzVision.az

More about:

-1747837442.jpg&h=190&w=280&zc=1&q=100)