For the first time in decades, both national parties have military veterans on the ticket. Both are candidates vying for vice president, so it’s natural for their experiences to be compared, contrasted and criticized. But the terms used in this conversation sometimes have different interpretations inside and outside the military.

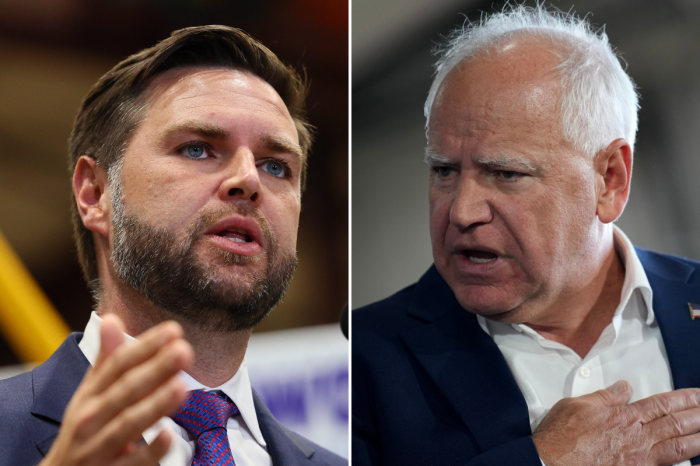

This debate has already turned nasty. There’s generally a code among veterans and the public that anyone who served in the military deserves thanks for their service, but if someone even vaguely claims to have done more than their record bears out, veterans become ruthless in their criticism. Add to that the high stakes of a presidential campaign in a highly-partisan election year and it was inevitable that political operatives would come at the service records of Republican nominee JD Vance and Democratic candidate Tim Walz.

I served as a Marine and have written about the military and veterans affairs for more than a decade. Just as people might not fully recognize the subtlety of a foreign language’s words and phrases, civilians frequently miss — or misinterpret — the language service members use to talk about the nature and scope of their service.

So to understand the current debate over the candidates’ service, it helps to decode some of the military terminology. Here are some words and phrases that have been part of the debate in recent days, and how they’re commonly understood.

“Deployed in support of…”

There’s confusion about whether Walz has claimed to have deployed to Afghanistan. He has gone on the record, for instance in 2007, saying, “I deployed in support of Operation Enduring Freedom.” That wording makes it absolutely clear to anyone who knows military terminology that Walz is not claiming to have been sent to Afghanistan on a combat deployment.

There is a misconception that a military deployment involves front-line combat, but that is not always the case. Troops from all branches deploy around the globe regularly, even during peacetime. During war, troops are often sent to bases and countries outside of the war zone to help keep the massive machinery of the Pentagon functioning. When troops do that they’re known as providing support for the war. It constitutes deployment.

Wars and military operations are known by technical, official names. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan also had multiple official names, changing as the scope of the war changed. Most of the time, the war in Afghanistan was called Operation Enduring Freedom. Walz’s careful wording about his deployment shows that he was keeping his distance from claims of being in Afghanistan. Walz has been documented holding signs that indicate he’s a veteran of Operation Enduring Freedom, but there’s no direct mention of Afghanistan.

Walz, though, has also appeared on television, for instance on C-Span, and nodded along as the host introduced him as a retired command sergeant major who’d deployed to Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. Former Rep. Peter Meijer, a Republican from Michigan and Iraq war veteran, has been dissecting on his social media account the complicated nature of understanding Walz’s record and the way he has handled discussing it.

Meijer has noted that Walz, on multiple occasions, doesn’t correct misimpressions of his service. It’s common practice for a veteran to mention in these situations that the host isn’t quite right and to correct the record. But at the same time, Meijer notes, interviews and conversations are human endeavors and it can be awkward and difficult to interrupt to make disclaimers. Meijer even notes that he was on a panel years ago and was introduced as an Iraq and Afghanistan veteran — though he’d never been deployed to Afghanistan. He said the free-flowing event didn’t easily allow him to jump in and correct the record, and soon enough the conversation moved on. Meijer has always been forthright about his service. He said he still regrets not saying anything during that panel, and that he had no intention of taking too much martial credit, but it can happen. Meijer told Politico what bothers him is that Walz has repeatedly not corrected those kinds of misinterpretations.

“Seeing Combat”

Neither Walz nor Vance saw combat during their time in service, and neither man has been documented overtly claiming such. In the military, seeing combat is an objectively quantifiable thing. This is a very simple description, but in short, to claim to have seen combat a veteran needs to have been in a place where an enemy attacked them in some way or they fought with the enemy. When a Marine sees combat they are awarded a Combat Action Ribbon. When a soldier sees combat they are awarded a combat badge. These awards go into a person’s permanent record and a ribbon or badge can be worn on their uniform.

Not every person who goes on a combat deployment necessarily sees combat. Simply put, a combat deployment is when someone is sent to a place where troops are engaging in operations. Walz deployed to Europe in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. This was not a combat deployment because there was no one fighting in Europe. Vance deployed to Iraq during the war, so he was on a combat deployment. But he did not see combat while he was there.

In his book, Hillbilly Elegy, Vance is careful to say he did not see combat while in Iraq, saying he was “lucky to escape any real fighting.” And recently in a fundraising email he made sure to distance himself from claims of combat saying, “I deployed to Iraq, did my duty, and I’m proud of my service. But I was lucky. There were some scary moments, but it wasn’t like you’d see in the movies.”

That disclaimer comes a day after he posted on X, formerly known as Twitter, “When I got the call to go to Iraq, I went.” Such statements could get tied up with preconceived perceptions of deployments and combat.

“I served in Al-Asad”

Similarly, Vance recently posted a message to the American troops injured in a suspected rocket attack on al-Asad, a major base in Iraq where U.S. troops are still deployed. Vance said in the message, “I served in Al-Asad.”

It’s true, Vance was at that base for his deployment. And it’s true that the base came under fire just days ago. But such bombardment is unusual and a deployment to Al-Asad, even during the height of the Iraq war, was not known for its danger and was, in fact, seen by many troops as a comfortable and relatively low-risk place to be. At the time Vance deployed, the base was known for its amenities like a gym and chow hall with ample food, sodas and ice cream.

Public Affairs

Vance was a public affairs Marine, someone who photographed and wrote about the military’s deployment in Iraq and whose work was published on military sites under his name at the time, James D. Hamel. Vance has said on multiple occasions that he saw no combat but that he did leave the base as part of his job.

Public affairs troops have a long history of deploying alongside front-line infantrymen, seeing combat and even being wounded or engaging with the enemy. This was not the case for Vance. In his book, Hillbilly Elegy, he wrote that the most memorable thing that happened to him when he was off the base was giving an Iraqi child a pencil eraser.

Vance shares a similar background with a previous, successful, vice presidential candidate: Al Gore was an enlisted journalist in the Army during Vietnam and wrote for Army publications.

“Weapons of war, that I carried in war.”

Walz has one documented instance people on both sides of the political spectrum seem to agree is claiming too much. When talking about gun violence he told a crowd, “We can make sure those weapons of war, that I carried in war, are only carried in war.” Walz did indeed carry these weapons of war as a soldier and became proficient in their use, but he did not carry one “in war.”

Vance has seized on Walz’s critical mischaracterization and asked during a recent press conference in Detroit, “Well, I wonder Tim Walz, when were you ever in war?” Vance and the Republicans have used Walz’s blunder as a double-pronged attack: They use it not only to question Walz’s service but also to deflect attention from the fact that Walz is a Democrat who’s an avid hunter and proficient with guns of all types including artillery, his speciality in the National Guard.

Command Sergeant Major

The rank structure of the military can be bewildering, even for those in uniform. It’s hard for many people to know the difference between enlisted, officer and warrant officer. Never mind trying to keep straight each branch’s insignia. In the Army, generally speaking, the highest rank an enlisted soldier can attain is sergeant major. Officers take a different career trajectory and the highest rank an officer can attain is general.

The vast majority of units in the military are commanded by an officer, but that officer has an enlisted counterpart known as the senior enlisted of a unit. (In the military, units are shaped by not only their commander but by the senior enlisted.) A sergeant major can be given the job (known in the military as a billet) of senior enlisted soldier and adviser to the commander of a unit. When that happens, the sergeant major is called the command sergeant major.

When troops reach a new rank they are required to complete what are sometimes called “career-level schools” or academic training specific to that rank. Walz retired from the National Guard before he completed that rank-specific training. In retirement he is a master sergeant, one rank below sergeant major.

Walz has said in the past that he retired as a command sergeant major. And while he left the service as a command sergeant major, he is not a retired command sergeant major. His language in this instance is imprecise.

The Harris-Walz campaign website features Walz’s service in his official bio. Initially it read that he retired as a command sergeant major. The site has since been changed to say he rose to that rank. The edited language is precise.

Vance was an enlisted Marine who left the service with the rank of corporal after four years of service.

“Abandoning” troops

Vance and other GOP operatives have claimed that Walz retired from the National Guard to avoid service in Iraq.

Here is what we know about that charge. Walz received his eligibiity for retirement in late 2002, according to the Minnesota National Guard. In February of 2005, Walz filed paperwork to begin exploring a run for Congress. In March, the National Guard said it could mobilize part or all of Walz’s battalion for deployment, according to a press release from Walz’s campaign. He said publicly that he would deploy if called upon to do so.

Two months later he retired from the Guard and said he would focus full-time on running for Congress. At the time of his retirement he was in his 40s, had served more than two decades in the Guard and had been home for just over a year after a deployment in support of Operation Enduring Freedom. He also underwent surgery for hearing loss related to his service, according to his campaign. His unit received official mobilization orders in June of 2005 and went on deployment in March 2006. He was elected to Congress that fall.

Walz has not publicly provided one key detail about his retirement — namely the specific date that he officially requested to leave the service. That information would allow the public to know if his unit was aware of a forthcoming deployment at the time he submitted paperwork to leave the military. Walz’s staff did not provide that date when asked for it by Politico.

In the Army, as in the rest of the military, very few things happen quickly. That’s especially true for mundane administrative matters. When a person retires, it takes time to process the paperwork and for all matters to be finalized. Likewise, only a few units in the Army are given short notice that they will be deploying. Two months would be considered a short timeframe from submitting retirement paperwork to actually retiring. The Guard generally recommends filing retirement paperwork 90 days prior to the date a person wants to leave the service.

Walz likely could have postponed his retirement and deployed with his unit to Iraq if he had pushed to do so. He has said he was willing to deploy if needed. One of the realities of the National Guard is that the odds are low a soldier will be called on to deploy overseas, but it is a possibility members accept when signing a contract. That being said, Walz had already put in more than 20 years and recently deployed when he put in his retirement papers.

It’s a tenet of the military that leadership can be replaced in any unit. While some in Walz’s unit have complained that he did not deploy, others note that he was replaced by another senior enlisted with ample time before that unit’s deployment.

“Stolen Valor”

Stolen valor has a precise, legal definition but it also has a broader meaning. Stolen valor technically refers to a federal law that has been strengthened over time, which makes it a crime to make a number of false claims about military service, mostly related to medals awarded in combat. But popular sentiment equates stolen valor with any claim of military service that can’t be proven through documented service.

Vance said at a press conference in Detroit, “What bothers me about Tim Walz is the stolen valor garbage.”

Stolen valor legislation is left up to interpretation because it covers not only egregious cases of someone wearing a fake uniform, but of other claims that might lead to someone getting a tangible benefit. The flexibility of the language around stolen valor, especially in popular culture, makes it easier to label someone as having stolen valor. But it can also diminish the impact of those criticisms.

The “Special Forces” cap

As part of the “stolen valor” attacks, Republicans have recently chastised Walz for wearing a ballcap emblazoned with an embroidered version of the Army Special Forces crest, claiming it’s disrespectful and dishonest for him to wear that cap.

The military community looks down on people who wear insignia they haven’t earned, but that anger is typically directed at people who wear the actual badges and insignia of a unit rather than a t-shirt or hat that might have been sold at a fundraiser or given as a token of appreciation.

When elected officials visit or interact with military units they’re often given mementos by the troops, such as caps. Walz’s campaign told Politico that he had been given the cap as a gift when he was a member of congress. Elected officials will often display those items and, if apparel, sometimes wear them. The military community frowns upon people who buy and wear gear from units, especially elite units, if they didn’t serve in them. But that line gets blurred when it’s an item given as a gift by a member of that unit and is usually just simply seen as a nifty hat with a good backstory. Walz has never claimed any Special Forces status. When a proud mom or dad buys an Army shirt to wear after their kid graduates boot camp, nobody chastises them for stolen valor.

Eating our own

The Walz-Vance conversation makes public a secret in the veteran community, that people are constantly measuring up their own service and trying to understand where they fit in the hierarchy of experience, of trauma, of sacrifice. I wrote about this phenomenon in my book, Bravo Company, which is about an Army company’s harrowing Afghanistan deployment and their return home.

In other words, veterans are sometimes apt to eat their own, which is to say they will respect anyone who served, but they want to make sure everyone claims their proper place in the pecking order. Woe to those who step out of line.

One of the men I chronicled in my book had been wounded in combat, served an entire career in the military and was the type of person who subscribed to the idea of the hierarchy of service. But after retiring he realized that everyone who served bears their own trauma and had their own experiences deserving of compassion and respect. He realized that veterans shouldn’t be so quick to attack each other.

What shouldn’t be lost in the conversation is that both Vance and Walz served their country honorably and had no marks against their records when they were in uniform. That’s the main thing that shouldn’t be forgotten. It gets said so much that it can be trite, but maybe in this case it’s particularly apt: Gentlemen, thank you for your service.

Ben Kesling is a former reporter for the Wall Street Journal where he covered military and veterans issues for more than a decade. He served as a Marine Corps infantryman and deployed both to Afghanistan and Iraq. He is the author of Bravo Company, a book about an Army unit’s deployment to Afghanistan.

More about: