But there are concerning technologies “only a few years, at best, away”, Walsh said, and with semi-autonomous systems, such as drones, “it would take very little to remove the human from that loop and replace them with a computer”.

Walsh and other members of the campaign painted a dire picture of uninhibited artificial intelligence taking root on battlefields and national borders. Unlike those needed for nuclear weapons, they said, the resources to create “killer robots” will only become cheaper and more available over time. With an online-bought drone, a smartphone and the right software, anyone could create “a little killer robot”, Walsh added.

Given the growing availability of robotics – and the already advanced state of artificial intelligence in the US and UK – the experts suggested that “killer robots” may end up having more in common with AK-47s than nuclear bombs.

“You’re going to see them being used in domestic policing, border patrol, riot control, not just armed conflict,” Steve Goose, director of Human Rights Watch’s arms division, told the Guardian. “The physical platforms already exist. It’s not science fiction, it’s a completely new way of fighting that revolutionizes all of this.”

“If we don’t [create rules], we will end up in an arms race,” Walsh said, “and the endpoint of that arms race is going to be a very undesirable place.”

Peter Asaro, a professor at the New School in New York, noted that without a human in control, machines fail to take in the unpredictable variables and context of war: “what’s the context, what’s the situation, is the use of force appropriate in this context and this target, and you can automate it but can you automate it well, and who’s responsible when it doesn’t operate correctly”.

“This will seduce us into warfare,” Walsh said. “It will be too easy, we’ll think that we can fight these wars cleanly, and as we have seen I mentioned with the drone papers, that is a deception because we actually aren’t able to make that kind of technical distinctions between combatant and civilian.”

Even with a human ostensibly at the helm, semi-autonomous AI make devastating mistakes, he observed. In the first Gulf war, Patriot missiles struck American and British aircraft, and recently leaked documents about the US drone program revealed a large number of assassinations performed without confirmation of who was killed in strikes.

“From a technical perspective, if you replace that human with a robot, you’re going to see even more mistakes,” Walsh said. He later told the Guardian that although artificial intelligence in controlled environments – a factory, a lab – can work quite well, “our stupid AI today is not as amazing as the human brain” in the unpredictable real world, much less the battlefield.

Ian Kerr, a professor of ethics and law at the University of Ottawa, compared the decision to give artificial intelligence the ability to choose targets and kill to “a kind of Russian roulette”, saying it would “cross a moral line that we’ve never crossed before”.

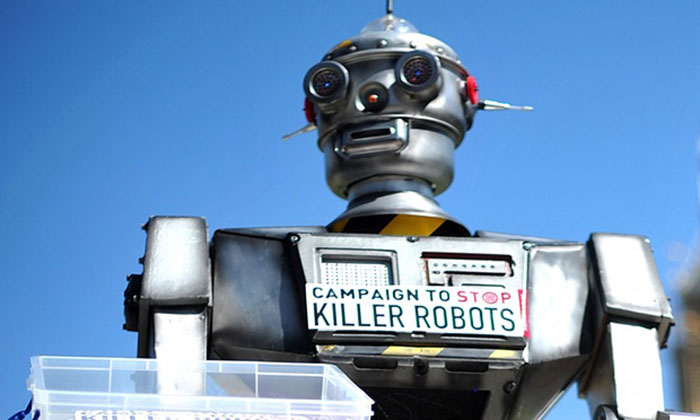

Campaign organizers insisted they were not scaremongering and defended the “killer robot” moniker, saying that the dangers are real and the phrase served them well in the staid world of diplomats and committees.

Goose said that Afghanistan and Pakistan – where hundreds of people, most of them civilians, have been killed in drone strikes in the past decade – have been particularly vocal supporters of the three-year effort.

The US, UK, Israel and South Korea have kept comparatively quiet on the issue; each country has advanced AI programs and ranks among the top spenders on their militaries. The US and UK have policies on military AI, but the activists, who want the UN to formalize talks on “meaningful human control”, said that both countries’ rules were too ambiguous.

Richard Moyes, a managing partner at the UK non-profit Article 36, said although the country has promised there will always be “human control”, it has not elaborated at all on whether that means a direct operator, a supervisor, simply someone who has activated the AI, or something else entirely.

Similarly, the Pentagon policy always requires an “appropriate” level of human control; a spokesperson did not immediately respond to a request for elaboration. And although in 2012 the Pentagon adopted a 10-year plan not to use fully autonomous AI, the measure allows senior officials to overrule it and does not affect research and development.

At the UN, the US and Israel have maintained they want “to keep the option open”, Goose said, and Russia and China have quietly watched talks while developing their own programs. “Nobody’s ’fessing up,” he said.

Should the UN formalize talks on 13 November, Goose said he expected an organized opposition to form. He expected, at minimum, that no country would block the renewal of informal talks, and said he hopes for results sooner rather than later.

“If we wait, the technological developments are going to overtake the diplomacy quite quickly,” Goose said.

More about: