For Libyans and Benghazi, though, the war never really disappeared. After their democratic hopes were kindled following the 2011 revolt against Muammar Gaddafi, Libya has steadily spiralled into chaos among a myriad of armed factions.

The North African state now has two rival governments, with two parliaments and even two state oil companies, each one backed by loose coalitions of armed forces mostly inspired by local or tribal loyalties rather than any concept of the state.

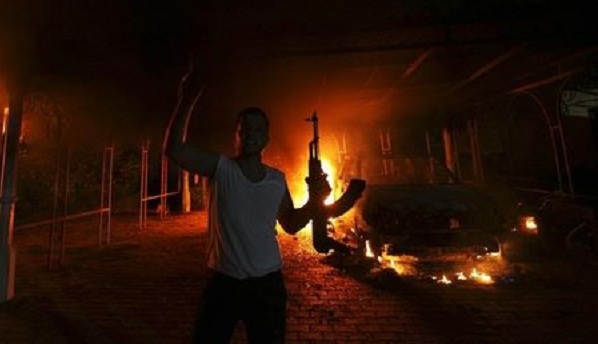

Benghazi, cradle of the uprising against Gaddafi, is now just one front in a many-sided war threatening to fragment the vast desert nation. For many in Benghazi, the consulate assault became a symbol for their own city’s slide into chaos.

“That attack proved to the world there was terrorism in Benghazi,” local activist Jamal al-Fallah said, remembering the 2012 assault on the compound. “It spread fear and confusion on to the Libyan streets.”

Since Gaddafi’s demise, heavily armed rebel brigades who once fought side by side against the strongman slowly turned against one another, allying with competing political poles and carving out fiefdoms in a war for control.

For a year, Tripoli has been held by Libya Dawn, an armed alliance of former rebels from the city of Misrata and Islamist-leaning brigades who have set up their own self-styled government and reinstated the former parliament.

The country’s internationally recognised government and elected parliament work from the east of Libya, backed by a loose network of armed factions, including a divisive former Gaddafi ally, General Khalifa Haftar.

In the vacuum, Islamic State has gained momentum, taking control of Sirte city and attracting foreign fighters to its ranks, while people smugglers profit from the chaos to send their cargoes across the Mediterranean from Libya’s coast.

The United Nations is trying to broker a unity government between the rival factions as a way to end the crisis, but months of tortured talks have yet to reach a final accord.

SHELLING, AIRSTRIKES

Clinton, a former secretary of state, testified before Congress about the incident in 2013. Now the frontrunner in the Democratic presidential primary campaign, she will appear on Thursday before a special House panel investigating the incident to answer questions about Benghazi as well as her use of a private email account while in office.

Benghazi was once a symbol of hope with images of British Prime Minister David Cameron and France’s then-president Nicolas Sarkozy triumphantly visiting the city in 2011. Now it is a symbol of prolonged fighting.

“The attack on the American consulate in Benghazi made the situation in Libya more complicated,” said a Tripoli lawyer who asked not to be named. “Benghazi, it’s the heart of Libya because they started the revolution against Gaddafi.”

For more than a year the forces of General Haftar, who backs the recognised government, has battled a coalition of Islamist fighters and former rebels for control of the eastern city.

As Haftar’s forces have advanced, some of the city has returned to normal, with restaurants and banks reopening. But fighting flows back and forth and shelling and air strikes have wrecked neighbourhoods. Rockets often hit civilian targets.

Even the former consulate compound itself has been damaged in the fighting, according to one military source in the city.

The city is divided into a patchwork of areas controlled either by Haftar’s forces or by their rivals, an alliance known as Majlis al-Shura.

Adding to the chaos, other Islamist militants proclaiming themselves loyal to Islamic State – the group that controls much of Syria and Iraq – have also started exploiting the security vacuum and attracting foreign jihadists to their cause.

Haftar’s Libyan National Army forces have used air support to help win back territory from Islamist fighters, including the airport area, eastern districts and several barracks that had been overrun last summer. But militant groups are holding out.

For some in the east, fed up with the militants’ control and roadblocks, Haftar is seen as a saviour of their city. For others, and for the Tripoli faction, the former general is waging an unsanctioned war on Benghazi in an ambitious personal drive for power.

More about: