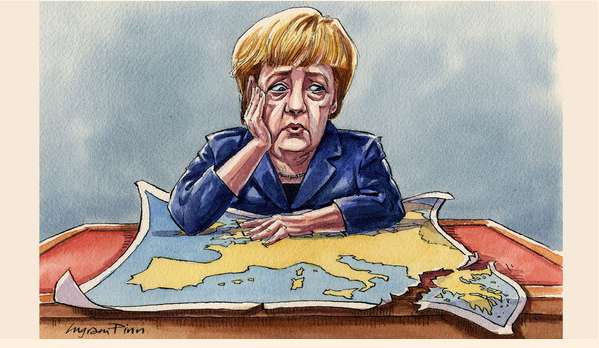

The end of the Merkel era is within sight - OPINION

But the refugee crisis that has broken over Germany is likely to spell the end of the Merkel era. With the country in line to receive more than a million asylum-seekers this year alone, public anxiety is mounting — and so is criticism of Ms Merkel, from within her own party.

Some of her close political allies acknowledge that it is now distinctly possible that the chancellor will have to leave office, before the next general election in 2017. Even if she sees out a full term, the notion of a fourth Merkel administration, widely discussed a few months ago, now seems improbable.

In some ways, all this is deeply unfair. Ms Merkel did not cause the Syrian civil war, or the troubles of Eritrea or Afghanistan. Her response to the plight of the millions of refugees displaced by conflict has been bold and compassionate. The chancellor has tried to live up to the best traditions of postwar Germany — including respect for human-rights and a determination to abide by international legal obligations.

The trouble is that Ms Merkel’s government has clearly lost control of the situation. German officials publicly endorse the chancellor’s declaration that “We can do this”. But there is panic just beneath the surface: costs are mounting, social services are creaking, Ms Merkel’s poll ratings are falling and far-right violence is on the rise. Der Spiegel, a news magazine, wrote this week that: “Germany these days is a place where people feel entirely uninhibited about expressing their hatred and xenophobia.”

As the placid surface of German society is disturbed, so arguments about the positive economic and demographic impact of immigration are losing their impact. Instead, fears about the long-term social and political effect of taking in so many newcomers — particularly from the imploding Middle East — are gaining ground. Meanwhile, refugees are still heading into Germany — at a rate of around 10,000 a day. (By contrast, Britain is volunteering to accept 20,000 Syrian refugees over four years.)

It is all such a contrast with the calm and control that Ms Merkel used to radiate, captured by her nickname Mutti (or “mum”). Throughout 2014, as Ms Merkel led Europe’s response to the eurozone crisis and Russia’s annexation of Crimea, German voters seemed more inclined than ever to place their faith in the judgment of the chancellor.

The refugee crisis, however, revealed another side to Ms Merkel. Some voters seem to have concluded that Mutti has gone mad — flinging open Germany’s borders to the wretched of the earth.

That, of course, is a major oversimplification. Germany’s decision last month not to return Syrian asylum-seekers to the first safe country they had entered was, in part, just a pragmatic acknowledgment that such a policy was no longer practical. Nonetheless, Ms Merkel was widely seen as having announced an “open door”. That impression persists, making Germany (along with Sweden) the EU country of choice for asylum seekers.

The only way to turn this situation around quickly would be to build border fences of the kind that the Hungarian government of Viktor Orban has constructed. Some German conservatives are now calling for precisely such measures. But Ms Merkel is highly unlikely to embrace the Orban option. She knows that such a policy could sound the death knell for free movement of people within the EU, and would also seriously destabilise the Balkans by bottling up refugees there.

Instead, Ms Merkel wants an EU-wide solution. But German plans for a compulsory mechanism to share out refugees across the EU — and for an emergency fund to share the costs — are encountering stiff resistance. As a result, Germany’s relations with its EU partners, already strained by the eurozone crisis, are worsening. The election of an anti-migrant government in Poland this weekend will not help.

Could Ms Merkel still turn the situation around? If the German government gets lucky, the coming of winter will slow the flow of refugees, providing a breathing space to organise the reception of asylum seekers and to come up with new arrangements with transit countries, particularly Turkey.

Should the chancellor regain control of the situation it remains possible that in 20 years’ time, she could yet be seen as the mother of a different, more vibrant and multicultural Germany — a country that held on to its values when it was put to the test.

However, if the number of refugees heading into Germany continues at its present level for some time, and Ms Merkel remains committed to open borders, the pressure for her to step down will grow. There are, at present, no obvious rivals. But a continuing crisis will doubtless throw some up.

Regardless of the chancellor’s personal fate and reputation, the refugee crisis marks a turning point. The decade after Ms Merkel first came to power in 2005 now looks like a blessed period for Germany, in which the country was able to enjoy peace, prosperity and international respect, while keeping the troubles of the world at a safe distance. That golden era is now over.