The star, known as LkCa 15, is similar to the sun, but only 2 million years old.

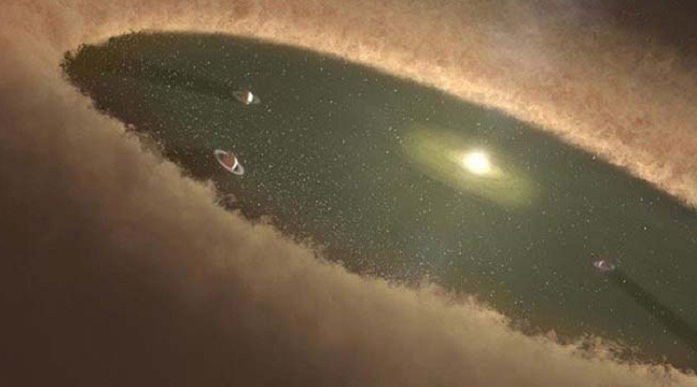

Unlike the 4.6 billion-year-old sun, LkCa 15 is still surrounded by a disk of gas and dust, the raw materials for planet building. Within the disk is a big gap, some 50 times wider than distance between Earth and the sun.

Astronomers previously suspected that a giant planet was orbiting in the gap. Research published in this week’s issue of the journal Nature confirms the find with infrared images of the planet, along with what appear to be one or two sibling planets.

Scientists also for the first time discovered the chemical footprints of superheated hydrogen gas streaming from the dust disk onto the planet, evidence that it is still forming, said Stephanie Sallum, a University of Arizona astronomy graduate student who led the team.

"This young system provides the first opportunity to study planet formation and disk–planet interactions directly," Sallum and colleagues wrote in Nature.

Of the nearly 2,000 confirmed planets discovered beyond the solar system, none are still in the formation stage.

In a related commentary also published in Nature, Princeton University astrophysicist Zhaohuan Zhu said the discovery will help scientists hone their theories about how planets are formed.

For example, more work is needed to explain the giant planet’s location and why it is still growing. Scientists also cannot account for how the planet is generating the massive magnetic fields that are believed to be responsible for super-charging its hydrogen gas feeding lines.

The discovery also demonstrates a technique to find other baby planets by searching for the telltale hydrogen gas emissions.

More about: