Many economists see a $20 per barrel oil price providing a short-term boost of 1.0 to 1.5% to global economic output. In a US context, Moody’s Analytics believes, the boost to consumption dwarfs the hit to investment via less mining exploration structures. Yet, moving beyond the short-term, there is widespread concern that persistently low oil prices might not be quite the bonus as previously thought.

The obvious entry point for such a discussion would be the finances of oil producing nations many of whom also happen to be major economies, and oil companies many of whom happen to be some of biggest listed companies in the world by market capitalization.

The aforementioned are in spot of bother with Brent ending 2015 around 36% lower on an annualized basis, and much of the current year being marked by extreme volatility. Whether we are talking sovereign ratings of oil producing nations, or credit ratings of individual oil companies, the wider market is pricing at least 2-3 notch downgrades, especially in case of emerging market oil producers.

It falls within range of how Moody’s and Fitch Ratings have already reacted with a series of downgrades. Expect more of the same according to Oxford Economics’ Head of Global Macro Research Gabriel Sterne.

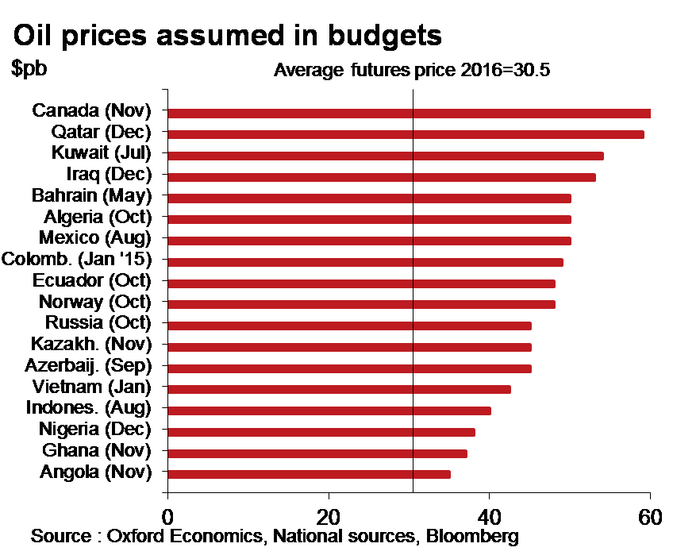

As oil prices are nowhere near $60 per barrel – deemed an equilibrium price in the eyes of many – and not expected to get near that level anytime soon, Sterne feels what is priced in national budgets of producing nations is on average 54% above market expectations for 2016 (see chart above).

“Many larger emerging markets remain heavily commodity dependent and fiscal buffers are mostly inadequate with half starting the downturn with troubling public debt to GDP ratios (>40%). Furthermore, governance rankings of producers are generally very weak.”

Momentarily digressing beyond the oil market, Stern says commodity slumps such as the current one are prolific causes of sovereign distress. “In our 1980s sample groups; 65% experienced debt increasing by more than 40% of GDP; and 68% defaulted (much higher if wealthy Gulf oil producers are excluded). Things could work out very badly this time round if commodity weakness persists.”

Moving beyond emerging markets oil exporters, there is a fair bit of anxiety across privately held oil exploration and production companies. Even if no one is meaningfully suggesting that current market conditions are similar to the 1980s just yet, all of the biggest 50 oil and gas companies have announced capital, operational expenditure cuts and job losses in order to save costs.

The situation is unlikely to change anytime soon, for the possibility of an ill-disciplined OPEC being forced into submission by lower oil prices remains remote. Recent farcical attempts at a production freeze by Saudi Arabia and Russia aptly demonstrate this. To quote Saudi Oil Minister Ali Al-Naimi, there is “less trust” between the big oil powers, making production cuts an unrealistic option.

That means US shale players, very much a part of the non-OPEC production uptick saga, will have to grapple with lower oil prices and face trials and tribulations of their own. Parts of the non-OPEC story are built on credit; so what’s bad for companies (and indeed countries) is bad for their creditors.

According to Wood Mackenzie’s research, based on an examination of 10,000 oilfields around the world, one barrel in every 30 oil barrels is being produced at a loss. In some cases, like the North Sea, the equation plummets to one in every seven barrels.

Anecdotal evidence from Wall Street and available data already suggests the ‘Big Four’ US banks are cutting what they lend to the oil and gas sector. However, the debt that is already out there and how it is serviced by struggling oil and gas companies is another worry altogether.

The deepening oil price slump will intensify pressure on US regional banks with high energy-concentrated exposures, according to Moody’s, six of which it has already placed on review for a downgrade.

The ratings agency added that increasing financial stress on oil producers and oilfield services companies will also erode the creditworthiness of banks with material direct loan concentrations to these companies.

Going beyond US shores, Moody’s expects the credit risk for banks in regions which are net oil-exporting will increase as their direct and indirect exposures to low oil prices raise the potential for asset quality deterioration. The ratings agency said that while lower oil price implications for global banks’ earnings and solvency appear broadly manageable, low oil prices could still test the creditworthiness of some banks across its global rated portfolio.

Moody’s analyst Frederic Drevon says, “We believe the ‘lower for longer’ scenario for oil prices is the base case scenario, and expect that banks in oil-exporting regions will likely see increased risk to creditors as banks’ adjust to this new normal.”

Nervous banks make markets nervous, with equities getting spooked by commodities to an extent unseen in recent memory, no matter how much the assetisation of the latter is trumped up gleefully or lamentably by commentators. For the record, commodities were the worst performing asset class of 2015. While the market has a capacity to handle good and bad news, the volatile start to the current oil trading year is worrying.

In an oil market witnessing a paradigm shift, one look at shipment trackers reveals US crude heading to Europe, Iranian oil heading to South Korea, and so the story goes with an almighty scramble for all else in between, and copious amounts in storage. The fact that Saudi Arabia and Russia led an initiative to ‘freeze’ production was laughable, because the former has run out of importing clients’ requirements meriting a production hike beyond January’s levels, while the latter does not have room to raise production further.

All it does is point to entrenched positions of oil exporters and a blood bath over the coming six months. The non-OPEC and OPEC melee will unquestionably have an impact beyond the oil market.

Commentators at Deutsche Bank Asset Management believe structural changes in the oil market and uncertainty about what they mean will span all market segments.

Stefan Kreuzkamp, Chief Investment Officer Deutsche Bank AM, says a deep-seated shift in thinking suggests oil is no longer the “familiar problem” that analysts evaluate using tried and tested fundamental data.

“Then there is the additional issue that recent market developments will increase concerns about the longer-term negative side effects of looser monetary policy. In this light, we have reviewed our forecasts for the most important equity market indices. The forecast for the S&P 500 Index is now 2080 points (previously 2170); for the Stoxx Europe 600 Index 370 points (390) and the MSCI Japan Index 1000 (1030).”

Where we could go from here remains a troubling thought, for it could all turn decidedly ugly if the global economy starts showing signs of cooling down over the coming months.

More about: