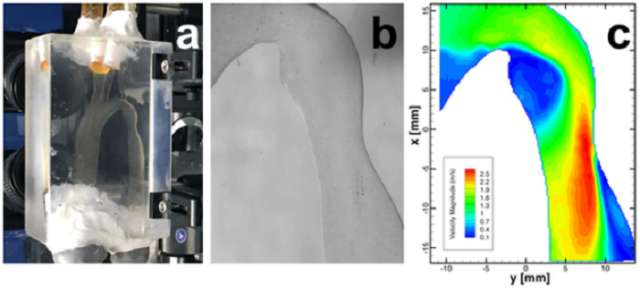

Its accuracy passed a first key test when physicists compared blood flow in the virtual aorta with the that of real fluid in a 3D-printed replica.

Flow patterns seen in the physical copy were a good match for the simulation.

This was the case even when the fluid passing through the plastic aorta - and the virtual blood passing through the simulated aorta - was moving in pulses, to simulate the way blood is pumped by the heart.

"We`re getting extremely close results both in the steady flow and the pulsatile, which is very exciting," lead researcher Amanda Randles, from Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, told BBC News.

She presented the findings - including the comparison with a 3D-printed aorta - this week at the American Physical Society`s March Meeting in Baltimore. The whole-body simulation itself was first unveiled at a computer science conference in November.

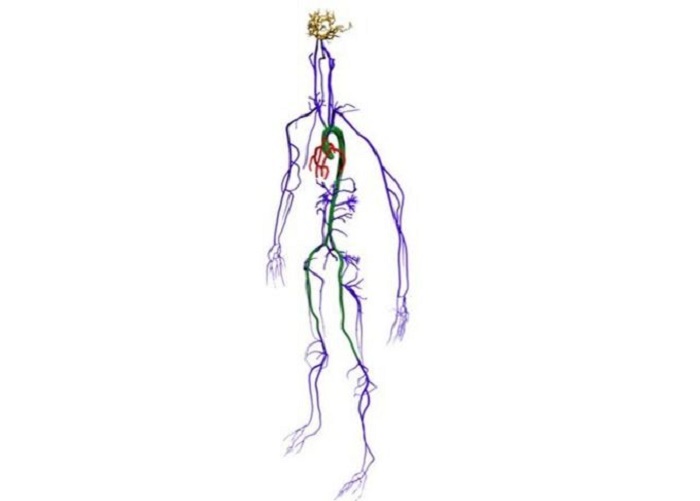

It is called "Harvey" - a tribute to the 17th-century physician William Harvey who first discovered that blood is pumped in a loop around the body. At the core of Harvey`s computer code is a 3D framework, built up from full-body CT and MRI scans of a single patient.

"It`s not a common practice," said Dr Randles of the full-body scan. "But if we have it, then we can extract the arterial network.

"We get a surface mesh representing the vessel geometry, then we decide what`s a fluid node and what`s a wall node, and then model fluid flow through there."

That modelling takes place on a supercomputer at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California.

"It has 1.6 million processors, so it`s one of the top 10 supercomputers," said Dr Randles, who worked in supercomputing at IBM before doing a physics PhD at Harvard, where she started work on Harvey.

"The first stage was simply a proof of concept: can we actually model at this scale?" Most other simulations, she explained, have focussed on smaller sections of the circulatory system.

"The largest, I think, before this, was maybe the aortal-femoral region - so, the aorta down to about the knees."

Modelling the flow inside every artery bigger than 1mm, at a resolution of 9 microns (0.009mm), a big step up.

One of the project`s aims is to test how different interventions in cardiovascular disease - such as stents or other surgical modifications - might affect the system more widely.

"We`ll be able to change the mesh file, representing the vasculature, to represent different treatment options," Dr Randles said.

"Typically you would look at the local haemodynamic changes, but by having a simulation of the whole body we can see how that would affect the large-scale haemodynamics."

To validate Harvey`s virtual blood flow against some real-world measurements, she added, the aorta - the biggest artery of them all - was an obvious choice.

"You can end up having turbulent flow, which you`re not going to see in other parts of the body.

"We figured if we can do it there, then we`ve a good chance - we`d believe the rest of the model."

So her team collaborated with that of David Frakes, an engineer at Arizona State University, on a physical comparison. They used 3D printing to create a plastic version of the scanned aorta, so that fluid could be pumped through it and its flow tracked using shiny particles.

Seeing a faithful reproduction of what the simulation had come up with, Dr Randles said, was "pretty rewarding".

"It`s pretty straightforward to calculate analytical solutions for flow in a pipe, or flow in a curved tube. But to make sure we`re really getting an accurate simulation in a complex geometry was much more difficult."

Next, she and her colleagues are turning their attention to the other half of the system; they are already building a mesh model of the same patient`s veins.

Ultimately, they hope to link the whole thing together with capillaries - the tiny vessels where red blood cells release their oxygen in single file - and even to move from fluid modelling to predicting the movement of all the individual blood cells.

If that can be done, then simulating the progress of single cancer cells through the bloodstream will also be a possibility.

But that will require a future generation of supercomputers, Dr Randles said, with at least a thousand-fold more power.

Her other hope is that their current high-level modelling will reveal the most important parameters to be measured and studied - so that patient-specific assessments can be done without the need for a supercomputer at all.

"We`re trying to figure out what parts of the model we need to include, when," she explained.

"The goal then would be to pare down the model and run it on something much more tractable."

More about: