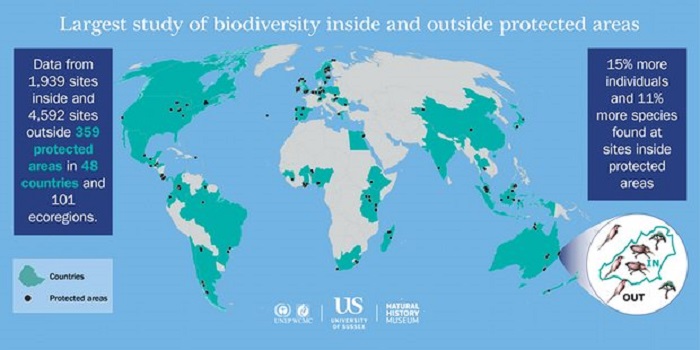

The study, carried out by the University of Sussex, the Natural History Museum and the UN Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre, analysed biodiversity samples taken from 1,939 sites inside and 4,592 sites outside protected areas.

“We have been able to show for the first time how protection effects thousands of species, including plants, mammals, birds and insects. This has provided us with important insights into these areas - which previous studies were not able to do,” said co-lead author of the study, Dr Claudia Gray, from the University of Sussex.

Protected areas are widely considered essential for biodiversity conservation. However there has been some doubt over their success, with problems including lack of effective management, increasing human pressures and inadequate government support.

Currently around 15% of the world’s land and 3% of the oceans are protected, and the Convention on Biological Diversity has pledged that this will rise to at least 17% of land and 10% of marine areas by 2020.

But these results demonstrate that protection zones do benefit a broad range of species, and governments must continue to recognise and support them, said Dr Jörn Scharlemann, from the University of Sussex.

“Protected areas do not currently benefit all species - but what we have shown in our study is they have the potential to help us conserve some of the most biodiverse areas on Earth - which is why they vitally need increased global support.”

The study used a relatively new global biodiversity database called Predicts (Projecting Responses of Ecological Diversity In Changing Terrestrial Systems), which contains field data from hundreds of scientists documenting how local terrestrial biodiversity responds to human impacts. The nearly four-year-old project has unprecedented geographic and taxonomic coverage, with more than 2.5m biodiversity records from more than 21,000 sites, covering more than 38,000 species. However this data only accounts for around 1% of all known species.

Previous regional or global studies of protected areas were limited to relying on information from satellite photos to examine changes in forest cover.

Prof Andy Purvis, one of the paper’s authors from the Natural History Museum, said: “This study shows how important questions in conservation biology can be tackled by joining forces. Hundreds of scientists from dozens of countries have generously shared their hard-earned data with us. Each one of those data sets is like a piece of a jigsaw: the overall picture only becomes clear when you have all the pieces and can put them together.”

The study, published in the journal Nature Communications, also showed that protection is most effective when human use of land for farming is minimised, suggesting better management of existing protected areas could more than double their effectiveness. The global protected area network was 41% effective at retaining species richness and abundance, the paper judged.

Dr Samantha Hill, from the UN Environment Programme’s World Conservation Monitoring Centre, said: “Humanity faces difficult decisions as to how best to protect biodiversity while providing for the needs of our ever-growing population. This study provides new understanding into the biodiversity found at the intersection of protected areas and human land-uses.”