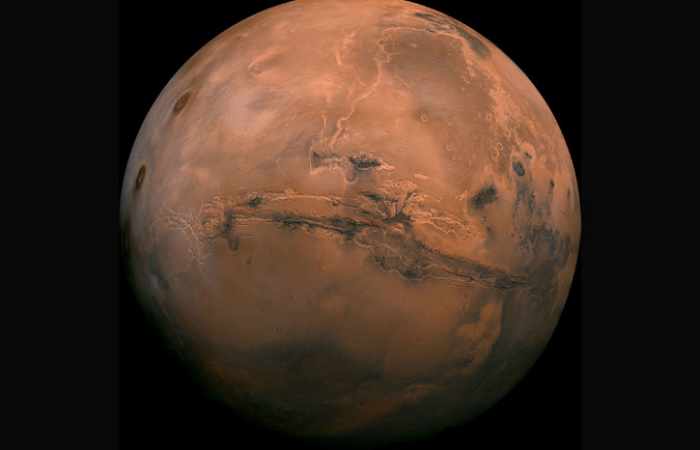

“If this can indeed be scaled up for mass production on Mars, then I would say we are lucky,” said Yu Qiao, a materials scientist and engineer at the University of California, San Diego, pointing out that soil on the moon does not share that ability. He and his colleagues published their work Thursday in the journal Scientific Reports.

Dr. Qiao and his colleagues experimented with a substance that is chemically and physically similar to what you might find on the surface of Mars, but is made from particles on our planet. They call it Martian soil simulant. Quite by accident, the team members found that with enough pressure they could mash the mock Martian dirt into bricks — no extraterrestrial kiln needed.

The technique, if it works with real Martian soil, could make it possible to develop building material on Mars without needing extreme heat, water or a binding agent. Though the bricks they created were small, they were stronger than steel-reinforced concrete, Dr. Qiao said.

His team had previously worked with an analogue for lunar soil, which needs a binding agent that acts like glue in order to be compressed into a brick. The idea behind that research was that one day astronauts would take the binding agent with them to the moon, mix it with the soil and then compact it into blocks that they could use to make structures.

After that work, his team set their eyes on Mars. They realized they could produce the same kind of bricks for the red planet with smaller and smaller amounts of their space glue, until they found they could make Martian bricks by using pressure without a bonding agent.

“I thought, ‘What is going on?!’” Dr. Qiao said.

The team members think that the iron oxide, which gives the soil its red color, acts like a glue to hold the particles together after it is subjected to enough pressure. Dr. Qiao said his next step was to investigate whether the technique could create larger bricks that could potentially build a house.

“The paper is an interesting step in the right direction of development of building material for future explorers,” said Jon Rask, a research scientist at NASA who was not involved in the study. He said he would like to see this research conducted under extremely cold and dry conditions that mirror Mars’s atmosphere to see if the results would hold up.

Henning Roedel, a doctoral candidate at Stanford University who studies technology for construction in outer space, said in an email that scaling the method could prove to be a challenge. Still, he called the technique an elegant solution to the problem of building on other planetary bodies.

“Buildings are rarely made from a singular material,” Mr. Roedel said, “and as we learn about more options available for future explorers and colonists, the better chances I think we have at succeeding in our first extraterrestrial colony.”

/NY Times/

More about: #Mars