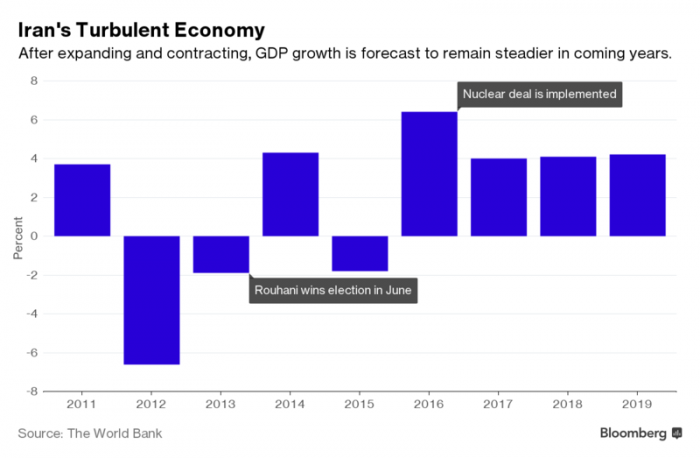

It’s from here that Iran’s religious conservatives are mounting a fight back against President Hassan Rouhani, who they blame for selling out to the western powers and failing to fix the economy. A poll showed Raisi, 56, who was often named in local media as a potential successor to Iran’s supreme leader, would face Rouhani in a runoff. The question is how far he can take the campaign beyond his hard-line, pious heartlands in the final week and cause an upset that would have global ramifications.

Should Raisi win, he would “perpetuate this siege mentality that has been passed from generation to generation rather than trying to build bridges and bilateral relationships,” said Sanam Vakil, an associate fellow at London-based international affairs institute Chatham House. “He would perpetuate the more conventional, conservative foreign policy of confrontation.”

Raisi’s speeches have been geared toward lower-income Iranians, highlighting what he says is a rising gap between rich and poor since Rouhani came to power. He is trying to occupy a space left by Rouhani’s predecessor, the populist Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, according to Foad Izadi, a member of the Faculty of World Studies at the University of Tehran.

It means he appeals to a constituency more concerned about scratching a decent standard of living than Iran’s foreign policy even with an escalating proxy conflict with Saudi Arabia and a cooling rapprochement with the West in the background. U.S. President Donald Trump has criticized the 2015 nuclear deal and his administration put Iran “on notice” in February following a ballistic missile test.

To an extent, that plays well for the hardliners, and voters like Sediqe Qavi represent Raisi’s target audience. She said times got harder for her under Rouhani’s leadership.

Qavi, 26, works full-time in a Mashhad store that specializes in headscarves and chadors and pools her monthly income with her 35-year-old brother, who works odd jobs in construction. She says they help support a family of five other siblings and their widowed mother on around 15 million rials ($460) a month.

“My problem with Rouhani is that nothing here has changed and things are getting more expensive,” Qavi said. “It’s not about making lots of promises, it’s more about making 10 and then making sure you fulfil at least five.”

Mashhad, the birthplace of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, embodies Iranian conservatism. It derives much of its income from the tomb of Imam Reza, a sacred figure for Shiite Muslims, drawing almost 30 million visitors a year.

Raisi spent most of his career as a judicial official and attorney, and Rouhani blamed him this week for bringing about “38 years of just executions and jailing.” But he’s viewed differently in Mashhad and among religious hardliners in Tehran, the capital, and the holy city of Qom.

Khamenei appointed Raisi in March last year to run the 200-year-old Astan Quds Razavi, one of Iran’s oldest and wealthiest religious institutions. While Rouhani also attacked the management of the Islamic foundation this week for being exempt from tax, Raisi’s stewardship of the shrine’s finances resonates with locals.

“He’s given a lot special care and attention to Mashhad,” said Rasoul Hekmati, 34, a father of two whose grocery store is a few blocks from the cleric’s central campaign office. “He’s really improved it and he’s really made himself stand out.”

Raisi’s campaign focuses on “dignity and work,” a message designed to reverberate with working class Iranians and those on the margins of the economy who have relied on government subsidies, which were cut under Rouhani. He also has enlisted his wife, an academic, to help bolster his image as someone who would also stand up for human rights.

The latest poll by the semi-official Iranian Students Polling Agency shows Raisi capturing 27 percent of votes, coming second to Rouhani’s projected 42 percent. If accurate, the two clerics would face off in a second round.

“I remember before he took over, around the shrine there were lots of beggars or old ladies asking for food and now the restaurant in the shrine has to give its leftovers to the needy,” said Mohammad Heydarpour, a retired office worker, as he drove through tracts of land he said belonged to the Astan Qods Razavi. “I just hope he’s not doing it for promotional reasons, because he wants to be elected.”

The key to whether Raisi can actually unseat the 68-year-old president is whether he can unite the conservatives behind him. Heydarpour said he will vote for Raisi or his conservative rival, Tehran Mayor Mohammad Bagher Qalibaf, who was born in a town on the outskirts of Mashhad.

“There is a segment of the population that is religious and more closely associated with the religious section of the government and they like him much more than Qalibaf,” said Izadi, the academic in Tehran. The problem for Raisi is that “he has a base that is very dedicated to him, but that base is relatively a small percentage of the population,” he said.

With 2.7 million people, Mashhad is the largest city in Iran after Tehran. Most of its high-rise buildings are high-end hotels catering to the millions of pilgrims. The streets surrounding the shrine are dominated by stores selling one of the area’s biggest exports, saffron, which is harvested from crocus farms in the province. Photographers hawk their studios where visitors can have their picture taken against a background of the shrine.

Rouhani’s supporters in the city see Raisi as someone who will roll back on freedoms introduced over the past four years. They include easing restrictions on theater and concert performances, and fewer “morality” police officers on the streets enforcing Islamic dress code. The leader of Friday prayers in Mashhad, who is also Raisi’s father-in-law, called for a ban on concerts in the city two years ago.

While they are confident their man will hold onto his lead, they say it will be by a much thinner margin compared with the landslide in 2013 that paved the way to the nuclear deal and Iran’s re-integration into the global economy.

“Mashhad will vote for Rouhani,” said Sina Omranian, 28, a political science student and head of the youth wing at Rouhani’s Mashhad campaign headquarters. “But personally I think we’ll win, though by a much smaller margin.”

/The Bloomberg/

More about: #Iranelections