The NASA-funded research was conducted on 34 astronauts who participated in short- and long-term missions to the International Space Station (ISS) or short trips on the space shuttle.

Each subject had their brain scanned with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) technology shortly before and after their mission, with the scans sent to neuroradiologists for interpreting.

None of the interpreters knew who the scans belonged to, and had no idea if the astronaut had been in space for as little as a week or two, or a number of months.

Sure enough, staying in space for long periods appears to increase your chances of developing some serious-sounding abnormalities.

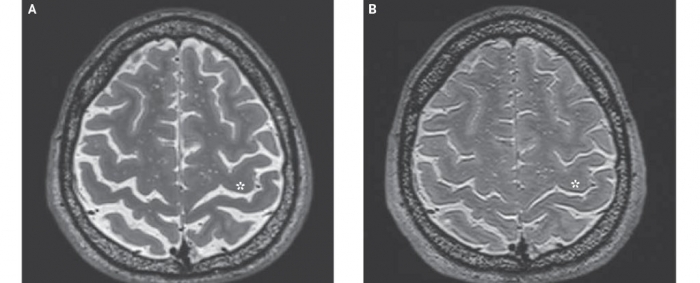

Of the 18 ISS astronauts who were classified as long-term space residents, 17 showed signs of a narrowing of the brain's central sulcus; a cleft that runs across the middle of the brain. This was seen in just three of the short-term travellers.

The sulcus divides areas of the brain responsible for motor control from those looking after sensory input.

An overall upward shift of the brain into the very top of the skull was seen in 12 of the long-duration astronauts, but in none of the short-term group.

Similarly, a shrinking of the cerebrospinal fluid channels at the top of the skull was seen in 12 of the long term group and just one of the short term.

While it all may sound alarming, it's actually hard to know what this narrowing means - whether it impedes the flow of cerebrospinal fluid or puts pressure on surrounding tissues.

"We don't know if these changes will continue to worsen with mission duration or if they may eventually reach a plateau," researcher Donna Roberts from the Medical University of South Carolina told CNN's Ashley Strickland.

More research is clearly needed, and future missions can provide that data. But the predictions aren't comforting.

"We hypothesise that upward brain shift and expansion of tissue along the top of the brain may in result in compression of adjacent venous structures along the top of the head," says Roberts.

"While we cannot prove it yet, we suspect that this may ultimately result in a decrease in the outflow of (cerebrospinal fluid) and blood from the head."

It's no surprise that microgravity would change how organs like the brain change shape, affecting the movement of fluids.

Time spent in free-fall produces a wide variety of changes on our biology, often affecting male and female anatomy in unique ways.

If you're familiar with astronaut lingo, you might have heard of the term "puffy head bird legs" to describe the condition of fluid hanging about in the upper body, making legs seem scrawny as the face swells.

Staying in space for half a year or more can alter the shape of our eyes, for instance, impairing our vision.

Oddly, not a lot of study has been done on the central nervous system.

Several years ago a similar piece of research also showed some significant changes to the volumes of various parts of the brain.

There is also evidence that the increased amounts of radiation showering down on astronauts can increase their risks of developing Alzheimer's disease.

Could the long trip to Mars hit them with a double whammy, building up damaging proteins that aren't efficiently whisked away thanks to narrow channels?

Space is hell on the human body, but then so were long ocean voyages just a few centuries ago.

It's clearly still early days for spacefaring humans, but understanding the problem is the first step in solving it.

More about: #Astronaut