Still-life painting has existed since time immemorial and offered us some of the most sublimely beautiful painting in art history. Yet for centuries it was dismissed by critics as merely an academic exercise in composition, colour and texture, of interest purely for its decorative qualities. A strict hierarchy saw history, portrait and genre painting as the most valued styles, followed by landscapes and animal painting with still-life placed ignominiously at the bottom.

This view held little sway, however, with the many distinguished patrons who collected the works, not to mention the artists who created them. Both were aware that this apparently lowly genre offered opportunities for moral contemplation, scientific study and even ground-breaking experiments into what art itself could be.

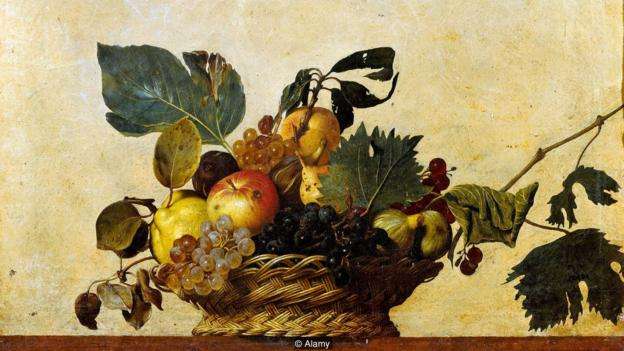

Caravaggio is best known for his biblical scenes and crepuscular shadows, but he also painted this highly detailed still life (Credit: Alamy)

Possibly the first description of still-life appears in Pliny’s History of Nature, in which he praises the ancient painter Zeuxis for creating grapes so real that birds would pick at them. It was the rediscovery of texts such as these during the Renaissance that inspired artists to try and recreate them, and the intellectual nature of the challenge which attracted patrons.

As Ángel Aterido, curator of a major exhibition of Spanish still-life painting at BOZAR, Brussels, explains, “the first owners of these paintings were people of a high intellectual level. The paintings went to their libraries not to their dining rooms.”

The Spanish painter Juan Sánchez Cotán created still lifes called bodegónes – these were much more austere than still lifes from Northern Europe (Credit: The Abello Collection)

Caravaggio’s celebrated Fruit Basket was painted for the Archbishop of Milan, as were some of Jan Brueghel the Elder’s most fabulous flower bouquets, while in Spain Juan Sánchez Cotán created works for the Archbishop of Toledo.

Elements of still life can lend themselves to spiritual expression – here, Diego Velázquez shows the preparation of a simple meal for Lent (Credit: National Gallery, London)

Although still-life is often associated with hidden symbolism, these early works were primarily concerned with rendering their subject in fine detail. The neutral background of Caravaggio’s Fruit Basket suggests he may even have been attempting to confuse his audience in the manner of his ancient forebears. However whilst Brueghel’s attention to detail saw him travel from city to city to paint individual flowers the fact that he, like many later Dutch flower painters, included flowers which bloom at different times within a single canvas, means that they could never be mistaken for the real thing.

Osias Beert turned subjects into symbols: the cherries and strawberries represent the souls of men while a dragonfly represents the devil, waiting to corrupt them (Credit: Alamy)

Cotán, meanwhile created a style unique to Spain, turning his exquisitely observed fruits and vegetables into mystical objects which demand contemplation by placing them in an austere window setting against a dark background.

Spirituality in stillness

The 17th Century saw still-life painting flourish and divide into many different sub-genres including fruit and vegetable studies, meal still-lifes and vanitas painting.

Fruit, vegetable and meal still-lifes were often imbued with religious symbolism. The Dutch painter Pieter Aertsen featured Biblical motifs in his market and kitchen scenes as a warning against excessive consumption and the idea was picked up by Velázquez, notably in Christ at The House of Martha and Mary. A young servant girl is seen crushing garlic to serve with fish, a Lenten meal emphasised by the presence of two eggs on a second plate. Behind her in what could be a picture within the picture, a mirror, or a window we see the titular scene. An old woman gestures to the servant girl emphasising that an active life is not enough and one must also be devout.

The spiritual is made explicit in Antonio de Pereda’s The Dream of the Knight, in which an angel shows a materialistic knight the true path to salvation (Credit: Rasbaf Madrid)

More subtle imagery can be found in paintings such as Osias Beert’s Still Life With Cherries and Strawberries in China Bowls. Educated collectors would recognise that the luscious fruits in their fine china bowls actually represented a fearsome battle between good and evil over men’s souls. The butterfly was their symbol of salvation whilst evil took the form of a Dragonfly, considered a subspecies of the fly and thus close to the devil. Cherries and strawberries were considered the fruits of paradise and thus represented the souls of men.

Around the time of his Disasters of War series, Goya painted still lifes that featured dead animals – perhaps as a memento mori (Credit: Museo Nacional del Prado)

Devout Catholics meanwhile would recognise in the careful spacing of Zurbarán’s quietly meditative Lemons, Orange and a Rose a reference to the Holy Trinity.

Vanitas symbols such as skulls originally appeared on the reverse side of donor portraits or panels of diptychs as a reminder of the transience of existence. As wealth increased amongst certain classes in Holland during the 17th Century, depictions of luxury goods were often tempered by the presence of a skull or an hour glass to remind the viewer that such luxuries would be of little use in the afterlife. Although the exquisite attention to detail for which these painting are famous suggests that both painter and patron most certainly took pleasure in them while they could.

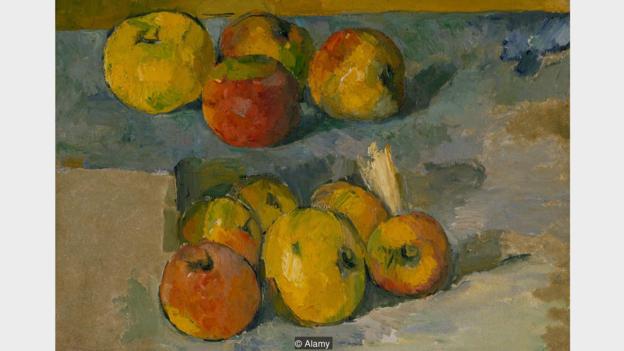

Cezanne revolutionised the still life with his abstract backgrounds, which seem to locate the fruit depicted in another realm (Credit: Alamy)

The Spanish had a unique form of vanitas called Desengaños del Mundo (Disenchantments of the World) related to the Ars Moriendi (The Art of Dying Well) texts which prepared Christians for Death. The Knight’s Dream by Antonio de Pereda, in which a sleeping man is shown with the luxurious contents of his dream spread out before him, is one of the most celebrated examples of this type. An angel hovering above offers a path to salvation.

From spirit to science

During the 18th Century an increased interest in the natural sciences encouraged some painters to move away from such symbolism in favour of a detailed observation of subject matter. In Spain the most important painter was Meléndez, whose finely observed studies of various foodstuffs can only evoke wonder.

Goya’s astonishing series of food still-lifes from the early 19th Century offers something wholly different. Painted in Madrid during the Napoleonic invasion and at the same time as he was working on The Disasters of War series, they feature birds, animals and fish whose humanised faces painted with agile, forceful brushstrokes cannot help but recall slain soldiers.

Most artists were beginning to abandon such humble motifs, though, in favour of those more suited to the growing ranks of the bourgeoisie who had become their prime patrons. Fantin Latour’s hazily sensual flower paintings became particularly popular.

Picasso’s Jug, Candle and Enamel Pan reduces the subjects to the most basic, but still recognisable, forms (Credit: Pompidou, Musée d'art moderne, Paris)

But although the subject matter may have narrowed, the methods of artistic expression were beginning to broaden. The Impressionists reinterpreted nature by painting its essence rather than its detail and while the daring colour experiments of Gauguin and Van Gogh may have been unappreciated at the time, they provided some of the most memorable still-lifes of the era.

In the early 20th Century Matisse used bold flat outlines filled with colour in his compositions while Bonnard and Vuillard added elements inspired by Japanese woodcuts.

But it was Cézanne who “put the genre on another plain,” according to Aterido. His experiments in colour, form and line would inspire Picasso who took his ideas and “elevated” them to another level, he says. By shattering conventional forms and recreating the world as he saw it in his Cubist paintings Picasso created something wholly unique and breathed new life into the still-life.

“When the avant-garde adapted the theme it changed everything,” says Aterido. Critics finally began to take notice.

And while the once revered history and genre painting had virtually disappeared from artists’ repertoires, still-life continued to flourish throughout the 20th Century with artists as diverse as Miró, Dalí, Morandi and Richter bringing constantly fresh approaches.

In the current century artists such as Sharon Core, Ori Gersht and Peter Jones are continuing to find new inspiration in the subject, using traditional motifs in a contemporary manner, which, just like their forebears, cause us to question the world around us.

The most humble of genres still has much to say.

BBC

More about: arts