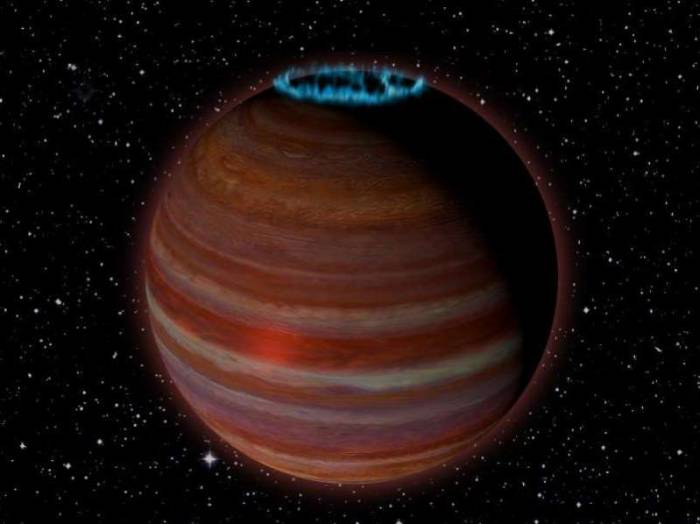

The rogue world is not attached to any star, and is the first object of its kind to be discovered using a radio telescope.

Both its mass and the enormous strength of its magnetic field challenge what scientists know about the variety of astronomical objects found in the depths of space.

“This object is right at the boundary between a planet and a brown dwarf, or ‘failed star’, and is giving us some surprises that can potentially help us understand magnetic processes on both stars and planets,” said Dr Melodie Kao, an astronomer at Arizona State University.

Brown dwarves are difficult objects to categorise – they are both too huge to be considered planets and not big enough to be considered stars.

Originally detected in 2016 using the Very Large Array (VLA) telescope in New Mexico, the newly identified planet was initially considered a brown dwarf.

Much still remains unknown about these astronomical bodies – with the first one only observed in 1995 – and the scientists behind the discovery were trying to understand more about the magnetic fields and radio emissions of five brown dwarves.

However, when another team looked at the brown dwarf data they realised one of the objects, called SIMP J01365663+0933473, was far younger than the others.

Its age meant that instead of a "failed star", they had found a free-floating planet.

The boundary often used to distinguish a massive gas giant plant from a brown dwarf is the “deuterium-burning limit” – the mass below which the element deuterium stops being fused in the objects core.

This limit is around 13 Jupiter masses, so at 12.7 the newly identified planet was brushing up against it.

As this was being established, Dr Kao had been conducting measurements of this distant object’s magnetic field – the first such measurements for a planetary mass object outside our solar system.

“When it was announced that SIMP J01365663+0933473 had a mass near the deuterium-burning limit, I had just finished analysing its newest VLA data,” she said.

Similar to the aurora borealis or northern lights seen on Earth, this planet and some brown dwarves are known to have auroras of their own – despite lacking the solar winds that traditionally drive them.

It is the radio signature of these auroras that allowed the researchers to detect these distant objects in the first place, but it is still unclear how they are being formed.

However, the research team’s analysis showed the planet’s magnetic field is incredibly strong, around 200 times stronger than Jupiter’s, and this could help explain why it also has a strong aurora.

“This particular object is exciting because studying its magnetic dynamo mechanisms can give us new insights on how the same type of mechanisms can operate in extrasolar planets – planets beyond our solar system,” explained Dr Kao.

“We think these mechanisms can work not only in brown dwarfs, but also in both gas giant and terrestrial planets,” she said.

Their research was published in The Astrophysical Journal.

The scientists said their study shows that auroral radio emissions can be used to discover more planets beyond our solar system, including more rogue ones not attached to stars.

The Independent

More about: space