KELT-9b is an "archetype of the class of ultra hot Jupiters that straddle the transition between stars and gas-giant exoplanets," a team of European researchers wrote in the journal Nature this week.

The distant gas giant, which has an equilibrium temperature of 3,770 degrees Celsius (6,830ºF), is the first time heavy metals have been detected in a planet's atmosphere.

That discovery adds to the already heightened interest around KELT-9b, which was first spotted last year by researchers examining the constellation Cygnus.

The planet's extreme heat meant researchers were able to detect iron and titanium atoms in the atmosphere as standalone atoms, not bound up in other molecules, researcher Kevin Heng wrote in an explanatory blog post. Because KELT-9b is so hot, the atoms don't condense into clouds in the atmosphere, but float around free.

"Clouds are probably absent because it is difficult to condense out any solid material from the gas at 4000 degrees Kelvin," he added.

On the spectrum

Iron and titanium "have long been an ingredient in the theory of exoplanet formation, but they have never been directly detected," Heng said. They were detected by examining light from the planet as it passed in front of its star. From fluctuations in that spectral data, Heng and his fellow researchers could spot evidence of heavy metals in the atmosphere.

"Different atoms or molecules have a fingerprint when you split the light into a spectrum," he told Space.com. "Given enough resolution, given good enough data, every molecule has a unique fingerprint."

As well as giving researchers valuable information about planet formation and why some objects become gas giants rather than stars, the technique used to detect the metal could potentially be repeated in future to search for bio-signatures, according to Heng.

Bio-signatures are evidence of life -- think Earth's green forests or the oxygen produced by them -- and could be the first sign of life outside of our solar system. But searching for them isn't that easy, we only have one example of what they could be, our own planet, and alien life could give off wholly different signatures.

Hot hot hot

If there is evidence of life to be gleaned from the techniques used to examine KELT-9b's atmosphere, it likely won't be on that particular planet.

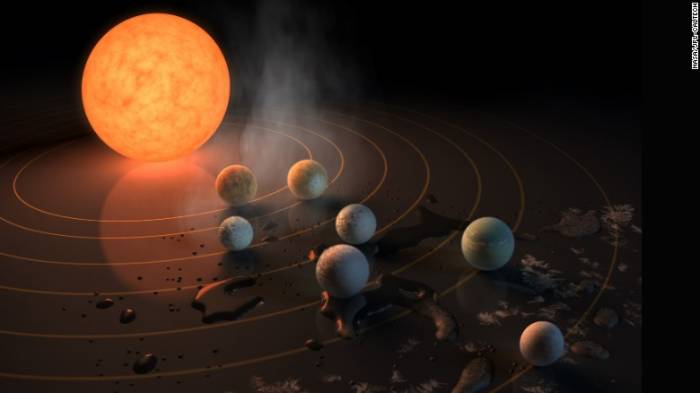

Nearly twice the size of Jupiter, KELT-9b is so close to its star that it orbits it every day and a half, rather than the year it takes Earth to go around the sun.

As well as being incredibly close, the star is also about twice as hot as our own, and two and a half times more massive. It's the hottest star of an exoplanet that we know of, researcher Scott Gaudi told CNN last year.

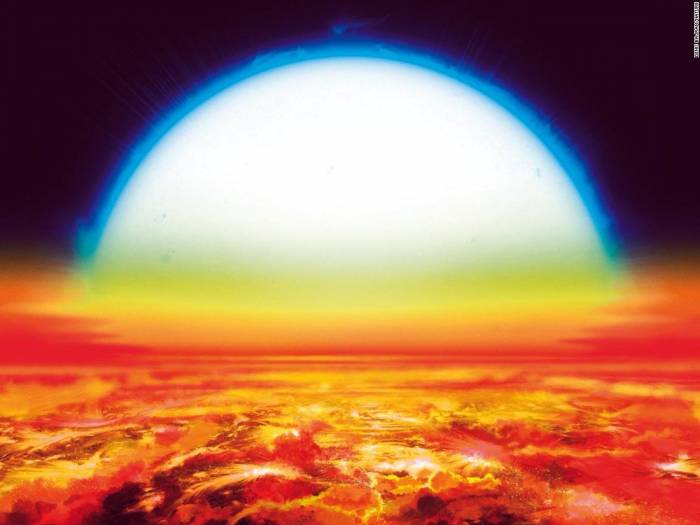

The heat of the star is such that it would appear white-blue to our eyes, while the planet would be bathed in orange and red light.

Due to its incredibly hot, luminous and close star, KELT-9b is being blasted by ultraviolet and high-energy radiation. If you poured water on the surface, it would immediately disassociate into oxygen and hydrogen, Gaudi said.

If this planet isn't strange enough, it also orbits perpendicular to its star, traveling around the star's poles rather than the equator. The researchers also believe that the orbit is like that of a top, getting closer and closer.

If the orbit doesn't eventually plunge it into the star, KELT-9b is likely to be absorbed nonetheless, as its host runs out of hydrogen in about 300 million years and expands to three times its size, swallowing up its planetary neighbors.

CNN

More about: planet