Earlier this month, Jamal Khashoggi – a Washington Post columnist and prominent critic of the Saudi government – walked into Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul to pick up documents that would enable him to marry his Turkish fiancée. Instead of receiving help from his country’s government, he was tortured, murdered, and dismembered by a team of its agents.

It is a shocking crime that raises some serious questions, not least regarding the appropriate balance between defending human rights and maintaining long-standing (and lucrative) alliances. More fundamentally, the sheer brazenness with which the Saudi government had Khashoggi killed – not to mention Western leaders’ weak response – has underscored for people around the world just how coldly calculated geopolitical machinations really are.

Transparency is usually a virtue to be encouraged. Here, however, the revelation comes at a cost. The belief that principles, values, and rules hold at least some weight in international relations has a stabilizing effect. As that belief is shaken – say, by the poisoning earlier this year of the former Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter on British soil – the global order is damaged, perhaps beyond repair.

The delegitimizing effect of such episodes is exacerbated by a broader abandonment of formalities – such as workplace dress codes and standards for communication – that has been fueled by the rise of social media. As our public and private lives are blurred, public figures are under pressure to appear as “real” and “normal” as our neighbors and colleagues. Even Pope Francis has released a rock album.

Of course, not all of these shifts are necessarily bad. The breakdown of formal structures can create space for independent thinking and innovation. The danger comes when no new framework emerges to help guide our behavior – and, more important, the behavior of our leaders – to ensure that it adheres to some shared values or reasonable expectations.

US President Donald Trump embodies this risk. Since coming onto the political scene, Trump has shattered expectations about how a US presidential candidate – and, subsequently, a US president – should behave. While there is nothing fundamentally wrong with a political leader communicating frankly and directly with his or her constituents, the tone and style of Trump’s delivery – largely via Twitter – is highly damaging. His below-the-belt insults, racist dog whistles, and unfounded attacks on the media and other democratic institutions are deepening political and social divisions, while diminishing respect for the presidency and the US more generally.

Trump’s unprecedentedly transactional – and highly erratic – approach to foreign policy is similarly destabilizing. To be sure, Trump’s deal-making was initially framed to some extent by broader values, especially increasing the “fairness” of US relationships, from security cooperation with NATO allies to trade ties with China. Despite Trump’s “America first” rhetoric, such actions seemed to be focused more on rebalancing the system than destroying it.

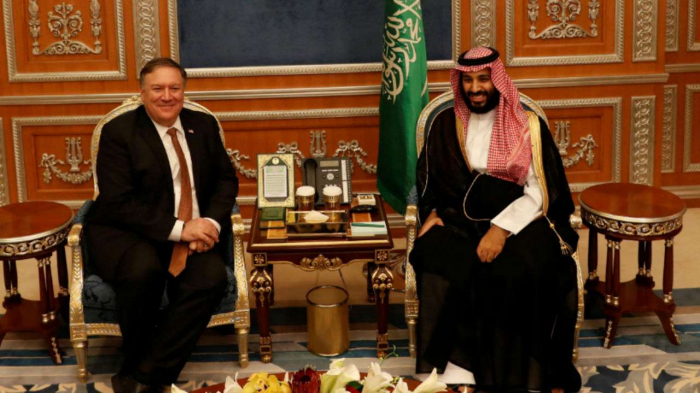

Trump’s response to the Khashoggi episode, however, is fully decoupled from any overarching values. To be clear, US presidents, together with European leaders, have been coddling Saudi Arabia for decades, and leaders worldwide often base their foreign-policy decisions on realpolitik, rather than moral considerations.

But this is the first time a US president has unabashedly acknowledged the purely transactional nature of their policy decisions. The Saudis, Trump declares bluntly, are “spending $110 billion on military equipment and on things that create jobs” in the US. “I don’t like the concept of stopping an investment of $110 billion into the United States.”

Notwithstanding the dubiousness of the figures involved, Trump’s comments are a bald statement of monetized interest. The comfort, even pride, with which he makes such statements indicates that we really have entered a new era, in which we cannot expect our leaders to clear even the low bar of trying to fit their decisions into a rules- or values-based narrative.

This is dangerous, because such narratives are vital to maintain the credibility of the global order and the support of domestic constituencies for it. Just like effective leadership and respect for the rule of law, a certain amount of faith in the system – even if it is qualified by frustration with inequality or impunity – is essential to its survival.

A world in which all that matters is the deal, in which there is no ethos guiding our actions and underpinning our governance systems, is one where citizens do not know what to expect from their leaders and countries do not know what to expect from their allies. Such an unpredictable and unstable world is not one that we should blindly accept.

It is not too late to respond to Khashoggi’s brutal murder in a way that reinforces, rather than undermines, the rules on which we all depend. German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s suspension of arms sales to Saudi Arabia is a good start, even if it was driven largely by her desire to shore up support for her Christian Democratic Union ahead of regional elections in Hesse; so, too, is the current pushback from Washington against a business-as-usual approach to Saudi Arabia.

But more must be done, with principled leaders declaring clearly that what happened in Istanbul is not acceptable. Otherwise, we will effectively be giving up the discourse of values and rules – a decision that could well leave us with no coherent and stabilizing discourse at all.2

Ana Palacio, a former Spanish foreign minister and former Senior Vice President of the World Bank, is a member of the Spanish Council of State, a visiting lecturer at Georgetown University, and a member of the World Economic Forum's Global Agenda Council on the United States.

Read the original article on project-syndicate.org.

More about: Khashoggi